Does Your Smartphone Need Cognitive Support Mode?

We live in a world where an iPhone has 47 different settings we can customize. Airplane mode. Dark mode for evening reading. Focus modes that silence work emails after 6 PM. Screen time limits. A bedtime routine that dims the display and mutes notifications. Even a driving mode that blocks texts while the car is moving.

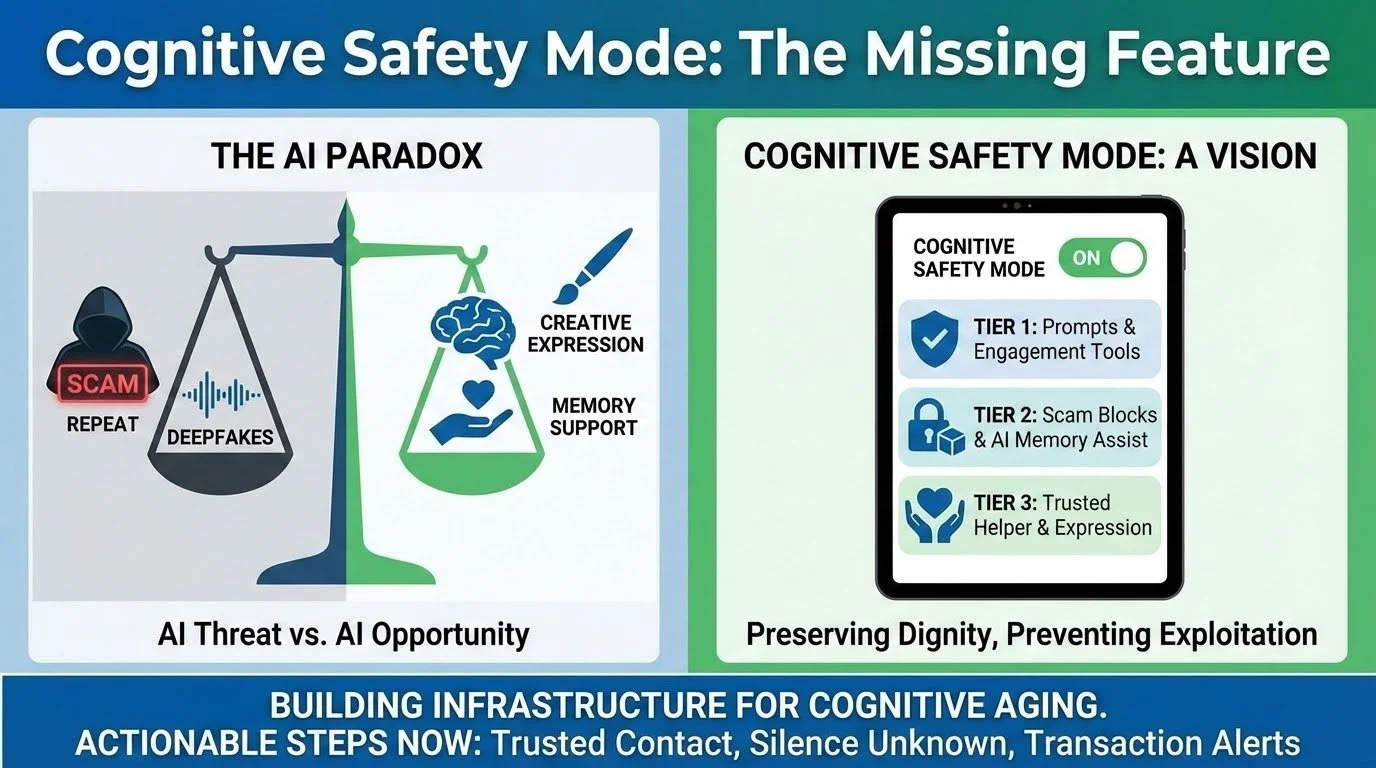

But there's no setting for the most predictable change of all: cognitive decline.

When loved ones start showing early signs of memory problems—missed bill payments, confusion about unfamiliar emails, susceptibility to urgent phone calls from "the IRS"—what do we do? Most of us improvise. If you see these changes in a parent, you might enable parental controls meant for children. If you have children, you have also struggled to do this for your children, too. Maybe you change passwords and stored them…somewhere. Hope YouTube does it for you? Set up transaction alerts. Create a patchwork of protections that feel simultaneously inadequate, confusing, and ill-fit: how do you know these protections will “work” for your loved one or yourself?

The technology exists. It just wasn't designed for what matters most.

The 7-Year Vulnerability Window

Here's what research tells us: financial and digital vulnerability doesn't emerge suddenly at dementia diagnosis. It begins years earlier—often 5-7 years earlier—in a window when people still have insight and could benefit from graduated support rather than wholesale loss of independence.

Studies tracking tens of thousands of older adults show that financial problems—missed payments, unusual transactions—emerge an average of six years before formal diagnosis. By the time someone is diagnosed with dementia, significant damage may already have occurred.

Adults over 60 lose an estimated $61 billion annually to financial exploitation. Investment scams alone accounted for $538 million in reported losses in 2024. And with AI making voice cloning and deepfakes trivial, the environment is getting exponentially harder.

AI Acceleration

In 2024, a grandmother in Arizona received a frantic call from her grandson. He'd been in a car accident. He needed $15,000 wired immediately for bail. He was crying. She could hear his voice breaking with fear.

She wired the money within an hour.

Her grandson had never been in an accident. The voice was generated by AI from a 30-second TikTok video he'd posted months earlier. Deepfake video technology can create persuasive footage of trusted figures—financial advisors, doctors, family members—saying things they never said.

We're entering an era where the warning signs we taught people to watch for—"does this email have typos?" "does the caller sound like your real grandson?"—no longer protect anyone. The exploitation techniques are evolving faster than human judgment can calibrate, even for people with intact cognition.

For someone with mild cognitive impairment? For someone whose executive function is quietly declining, whose ability to update beliefs in light of new information is compromised, whose processing speed can't keep pace with rapid-fire persuasion tactics? The current digital environment is a targeting system optimized to exploit exactly their vulnerabilities.

The same AI that makes exploitation easier could also make protection possible for the first time. Machine learning already powers sophisticated fraud detection at financial institutions. Behavioral anomaly detection can identify unusual spending patterns, out-of-character transactions, merchant categories associated with scams. The technical capability exists to build protective scaffolding around cognitively vulnerable adults.

But the scaffolding doesn't exist as consumer-facing technology. Not in any coordinated, accessible, appropriately-calibrated way.

We Need AI For Our AI

If you search for solutions today, here's what you might find:

Apple's Assistive Access creates a completely simplified iPhone interface with large icons, minimal apps, and controlled entry/exit via passcode. It's thoughtfully designed—for severe cognitive disabilities. For someone with MCI who still manages most of their life independently but needs guardrails around high-risk decisions, it's far too restrictive. It's a binary switch when what's needed is a dimmer.

Third-party simplified launchers for Android phones—BIG Launcher, BaldPhone—reduce visual complexity and increase touch target sizes. Helpful for navigation, useless for preventing wire transfers to scammers.

Financial monitoring services like EverSafe and Carefull use AI to detect unusual transactions and alert designated family members. They're valuable tools. They're also boutique services that require families to know they exist, navigate signup, pay monthly fees, and integrate them into a care plan. Only a small fraction of at-risk families ever find them. Most discover them after exploitation has already occurred, if at all.

FINRA Rule 2165 permits financial institutions to place temporary holds on disbursements when they suspect exploitation. Rule 4512 requires firms to make reasonable efforts to obtain a Trusted Contact Person who can be notified when there are concerns. These are meaningful regulatory protections. Most families have never heard of these rules. Most financial advisors don't proactively implement them until a crisis forces the conversation.

There’s no standardized smartphone-based “Cognitive Support Mode” or tool that automatically:

detects early cognitive changes,

intervenes to prevent financial or digital exploitation,

and adapts interfaces based on cognitive ability.

What "Cognitive Support Mode" Could Be

First, smartphones do not appear to cause dementia. In fact, engaging with digital tools may even help maintain cognitive function. The problem isn’t technology use — it’s that technology does not adapt as cognition changes. Imagine if it did. When someone received an MCI diagnosis, their neurologist could say: "One thing we know is that financial and digital vulnerability tends to emerge in this stage. There are protections we can enable now. Let's talk about Cognitive Support Mode for you."

Not a single on/off switch. A graduated system that maps to the trajectory of cognitive decline, configured collaboratively with clinical input, adjustable as needs change.

Tier 1: Enhanced Awareness (MCI with intact insight)

The person retains decision-making capacity but could benefit from prompts and friction at decision points:

Confirmations for high-risk actions: "You're about to wire $5,000 to an account you haven't used before. Call [Trusted Contact] to confirm this is legitimate."

Scam detection overlays: When an email exhibits phishing characteristics—unfamiliar sender, urgent language, request for credentials—a banner appears: "This message has patterns commonly seen in fraud attempts."

Transaction summaries: Weekly digest to both the person and a designated family member showing spending patterns, new payees, unusual merchants.

Cooling-off periods: For large purchases or irreversible transactions, a 24-hour delay with easy cancellation option.

The principle: Informational, not restrictive. The person remains in control but gets decision support at critical moments.

Tier 2: Graduated Restrictions (MCI progressing, partial insight)

As capacity declines, more structural guardrails become appropriate:

Merchant category blocks: Disable purchases of gift cards (the #1 scam payment method), block cryptocurrency platforms, restrict wire transfers.

Dual-approval requirements: Transactions over a configured threshold require confirmation from a designated person before processing.

Simplified interface options: Reduce app access to essentials, increase font sizes and contrast, eliminate notification overload.

Velocity limits: Flag rapid sequences of transactions or interactions with unfamiliar contacts as requiring review.

The principle: Preserve autonomy where safe, add guardrails where risky. We want to make routine decisions independently, but high-stakes actions could be protected.

Tier 3: Supported Decision-Making (early dementia, fluctuating capacity)

When capacity is significantly compromised but the person still engages with technology:

Trusted helper mode: A designated trusted helper receives real-time notifications of high-stakes activity and can intervene before decisions are made.

Curated access: Only pre-approved apps and contacts available. New apps or contacts require helper approval.

Read-only sensitive functions: Can view sensitive information, cannot take action.

Voice verification for high-stakes decisions: "To confirm this wire transfer, please call your designated contact at [number]."

The principle: Maintain engagement while preventing exploitation. The person isn't locked out of their digital life, but significant decisions involve support.

Critical Design Elements

For any of this to work—to be ethical, to preserve dignity, to actually protect people—certain design principles are non-negotiable:

Configurability: Not one-size-fits-all. A clinician and family collaborate to set thresholds, restrictions, and notification recipients based on individual assessment. What's appropriate for one person with MCI is patronizing for another.

Transparency: The person knows what protections are in place and why. Not surveillance, but disclosed support. "Transaction alerts are enabled because we agreed this would help catch unusual activity early."

Reversibility: The person can appeal restrictions. Involve the clinician in reassessment. Graduated protections shouldn't become unilateral control.

Privacy-preserving: Alerts about concerning patterns, not keystroke logging. Monitoring without surveillance.

Progressive activation: Start with minimal restrictions, escalate only as needed, de-escalate if capacity improves (medication adjustment, treatment of depression, resolution of delirium).

The technical components exist:

AI behavioral anomaly detection is already deployed for fraud prevention at financial institutions

Apple, Google, and Microsoft already build sophisticated accessibility frameworks

Clinical assessment tools to calibrate appropriate protections exist and are validated (though in healthcare, we sometimes deploy first and validate later)

Why It Doesn't Exist

Here are some common obstacles:

Liability exposure: What if "Cognitive Support Mode" fails to prevent a scam? Lawsuit. What if it's too restrictive and the person loses money because they couldn't execute a time-sensitive transaction? Lawsuit. The safest legal strategy is to do nothing, let families improvise, and disclaim responsibility. Are you disclosing cognitive status by opting in to “Cognitive Support Mode” and are you protected?

Market uncertainty: Who pays for development? Is this a premium accessibility feature? A healthcare intervention covered by Medicare? A family-purchased service? The business model isn't obvious. And there's stigma—will people actually adopt something called "Cognitive Support Mode," or will they avoid it?

Clinical complexity: Cognitive decline isn't binary. It fluctuates. It varies across domains—someone might retain excellent language skills while losing financial judgment. Who certifies someone "needs" Cognitive Support Mode? What's the threshold? How do we handle the person who refuses protections despite clear vulnerability?

Fragmentation: No single entity controls the digital ecosystem. Apple makes the phone OS, but Gmail is Google, banking apps are each institution, shopping happens across dozens of sites. Building comprehensive protection requires coordination across competitors with different incentives and technical architectures.

These aren't trivial problems.

We figured out how to build accessibility features for blind users across competitive platforms. We created standards for wheelchair accessibility in physical environments despite massive coordination challenges. We developed graduated driver's licensing for teens despite liability concerns.

The question isn't whether this is hard, but whether it matters enough to solve.

What Can We Do?

We can include digital safety assessment like Dr. Peter Lichtenberg has done to help prevent scams and fraud and to help those impacted by financial exploitation (Older Adult Nest Egg: https://www.olderadultnestegg.com/). Document not just that someone has MCI, but what specific vulnerabilities exist and what protections are appropriate. Write prescriptions for technological accommodations the same way you'd prescribe physical therapy or occupational therapy. Become comfortable saying, "Based on your assessment, I recommend enabling these protective features."

Don't wait for the perfect solution. Use what's available now—designate Trusted Contacts at financial accounts, enable call blocking on smartphones, set up transaction alerts, consider monitoring services. Seek out clinicians who understand this domain.

The Other Side of AI: Cognitive Support

AI isn't only a threat. The same technology that enables exploitation also opens remarkable possibilities for cognitive engagement and self-discovery: AI as creative partner, memory companion, and tool for maintaining cognitive health.

AI-powered creative expression could enable older adults—including those with MCI—to engage in artistic activities that would otherwise be inaccessible. Generative image tools let people with limited mobility or artistic training create visual art. AI music composition tool could enable musical expression without years of training. Voice-to-text and text-to-speech break down communication barriers. AI companions could engage users in conversations, suggest activities, and remember past interactions. Users interact with these systems 30+ times daily. These would not be replacements for human connection, but they could be bridges during periods of isolation, prompts for engagement, memory aids. Perhaps most intriguingly, AI could help people see their own cognitive and emotional patterns. Speech analysis could detect subtle changes in language complexity, processing speed, emotional tone—changes that might signal early decline but be invisible to the person experiencing them. Rather than waiting for crisis, AI could provide gentle feedback: "You might want to talk to your doctor about these patterns I'm noticing."

Could the same AI that threatens exploitation also enable self-advocacy?

Imagine an AI system that helps someone with early MCI:

- Track their own decision-making patterns over time

- Identify situations where they feel confused or pressured

- Practice recognizing scam scenarios in low-stakes environments

- Maintain creative expression as other abilities decline

- Document their values and preferences while insight remains

The paradox: AI could both enable the scammer who clones a voice and empower the person with MCI who uses AI tools to maintain agency, creativity, and connection longer. I would argue we want something like supportive AI, which operates transparently, in partnership, enhancing remaining abilities rather than exploiting declining ones.

The conversation about "Cognitive Support Mode" isn't just about blocking bad actors. It's about building infrastructure that enables the beneficial uses of AI while protecting against the harmful ones. The technology is neutral. The design choices matter.

A Role for Cognitive Stewardship

Here's the uncomfortable truth: even if every tech company committed tomorrow to building Cognitive Support Mode and we figured out how to protect people who use it, it would be 2-3 years before coordinated solutions reached consumers. Product development, standards negotiations, and clinical validation takes time.

Families facing this now don't have 2-3 years to wait.

We can conduct comprehensive digital safety assessments that go beyond generic cognitive screening to identify specific exploitation risks. It means helping families implement the fragmented protections that exist today—Trusted Contact designation, graduated financial controls, device-level safeguards, monitoring systems—in a coordinated way that preserves autonomy. It means creating decision rules for when to escalate protections and how to have those conversations without destroying trust.

It's the bridge between "research shows vulnerability emerges six years before diagnosis" and "here are the three things you should do this week."

The technology will get better. The evidence base will improve. Coordinated solutions will eventually emerge. But millions of families are in the vulnerability window right now, today, improvising their way through a landscape that wasn't designed for them.

They need guides who understand both the cognitive neuroscience and the practical tools. Who can assess where someone is on the trajectory and calibrate appropriate protections. Who can translate clinical expertise into actionable family plans.

The Question We Face

Cognitive Support Mode doesn't exist, but it can. We could build it.

But even when we do, we'll still need the human expertise to calibrate it appropriately, to implement it ethically, to balance protection with dignity.

The future isn't choosing between technology and clinical judgment. It's both.

The question isn't whether Cognitive Support Mode should exist.

The question is: What do we do for the millions of families who can't wait?