Who's Really Coordinating Cognitive Care? It Matters.

Yesterday, I shared my upcoming Treasure Coast Cognition launch with my friend group. There was immediate reaction - and the need was clear. I received a direct message from someone I'll call Sarah:

"I'm going to share this with my friend Rachel - her dad was just recently diagnosed. We were just having a conversation about this. Amazing work you are doing."

Sarah's message isn't just a nice comment. It's a data point in a pattern I've been observing since this project has been in development - a pattern that has profound implications for how we think about cognitive health services.

The Pattern in the Data

I've observed a striking pattern in engagement:

Approximately 70% of my social media responses come from women

Every consultation inquiry has been initiated by a woman

The comments consistently say "I wish this existed when my mom/dad was going through this"

The direct messages come from daughters coordinating for parents, wives coordinating for husbands, women leading initiatives in the community

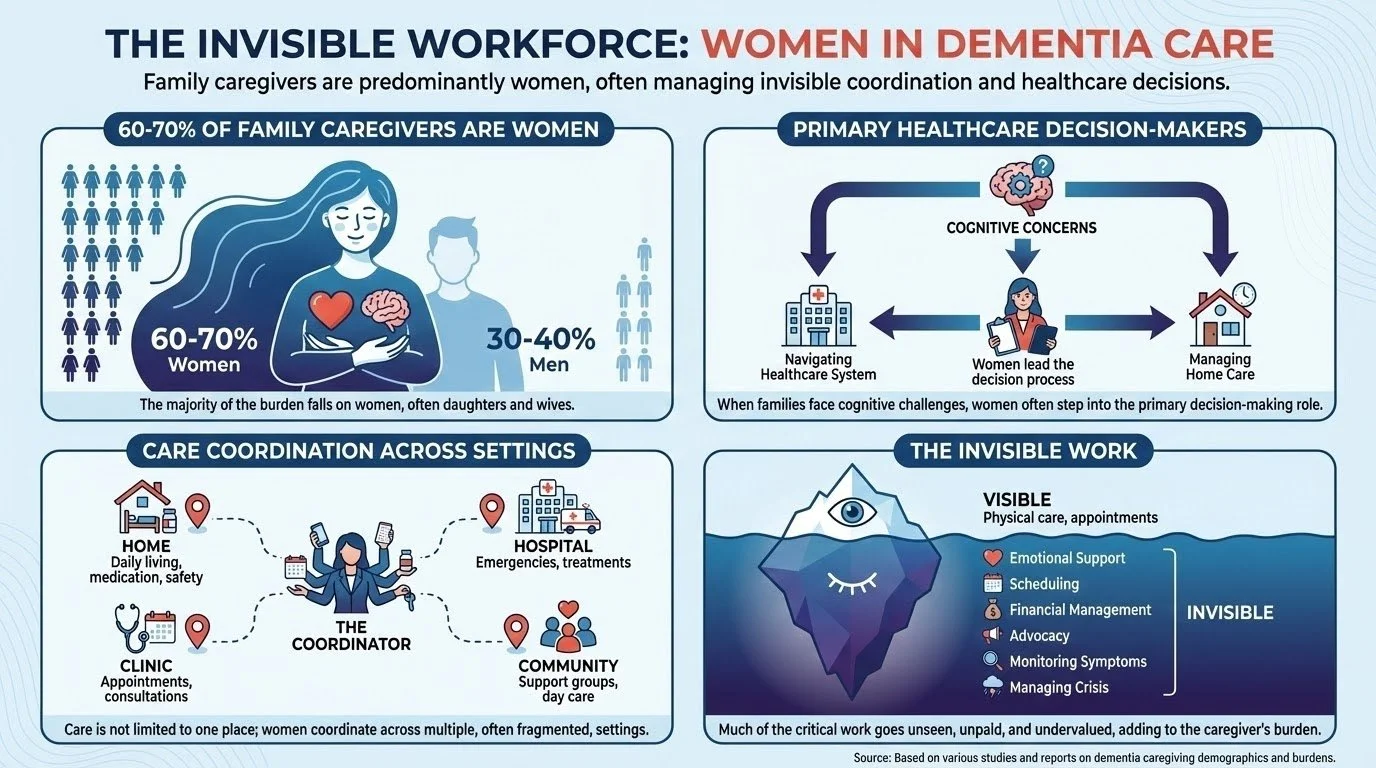

This isn't just my anecdotal observation. It aligns with extensive research showing that 60-70% of family caregivers for people with dementia are women. It is often women who make healthcare decisions when families face cognitive concerns.

The Reality of Family Dynamics

Even when the patient experiencing cognitive changes is male, women are disproportionately the ones who:

Notice the changes first. Subtle shifts in memory, judgment, or personality don't always announce themselves dramatically. They emerge in everyday interactions - forgotten appointments, repeated questions, uncharacteristic financial decisions. The person managing the household calendar, coordinating social plans, and maintaining family connections is often the first to notice something's different.

Initiate the conversation. "We should get this checked out" is rarely an easy conversation to start. It requires navigating denial, fear, and sometimes anger from the person experiencing changes. It requires overcoming the "I'm fine" response and the family's collective wish that everything is okay.

Research and vet options. Who's Googling or asking AI about "memory problems" at 11 PM? Who's calling doctor's offices to ask about wait times? Who's reading reviews and asking friends for recommendations? In most families, it's the daughter or wife.

Coordinate the actual care. Scheduling appointments, taking time off work to provide transportation, sitting in waiting rooms, asking the doctor questions, implementing recommendations, managing medications, following up on referrals - this is invisible labor, and it's disproportionately carried by women.

Manage the emotional complexity. The fear, the grief, the uncertainty, the family dynamics, the tough conversations about driving or finances or living arrangements - someone has to hold space for all of this. That someone is usually female.

What the Healthcare System Does Instead

Despite this reality, here's how most cognitive health services operate:

We direct our questions to the person with the concerns, even when the family member brought them to the appointment.

We schedule around the person with the concerns, without recognizing that the coordination burden falls elsewhere.

We measure outcomes in patient-centered terms, without acknowledging the toll on the person doing the coordinating.

We miss the person who's actually doing much of the work.

The Gap This Creates

When a family first notices cognitive changes, they typically face:

Long wait times. Memory clinic appointments often have wait times of 12 months, with some communities facing even longer delays. By the time you get seen, the trajectory has often progressed significantly.

"Just wait and see" responses. Primary care physicians, stretched for time and working within a system that rewards acute care over proactive monitoring, often default to reassurance rather than early intervention.

One-time evaluations with no ongoing guidance. Even when families do get a neuropsychological evaluation, it's typically a snapshot assessment with recommendations but no active monitoring or support through the changes ahead.

The coordination burden falling on whoever has bandwidth. And in most families, that's the daughter who lives closest, the wife who retired first, the adult child who has the most flexible work schedule. Usually women.

The Multi-Year Journey We're Ignoring

Research reveals a predictable but frustrating pattern in the journey from first concerns to formal diagnosis:

First, 2-3 years of family members noticing changes and wondering if they should be concerned. Subtle shifts in memory, repeated questions, uncharacteristic decisions - changes that prompt the question "is this normal aging or something more?" Studies from memory clinics across multiple countries show families typically notice symptoms for 1-3 years before seeking professional assessment.

Then, 6-12 months (maybe longer) waiting for a memory clinic appointment . Even after deciding to seek help, families face substantial wait times. Some communities have waits extending even longer, and primary care physicians often default to "let's wait and see" rather than proactive monitoring.

Then, if Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) is diagnosed, it could be an additional 7 years of uncertainty about what comes next. During the MCI stage - which can last 2-7+ years depending on individual factors - families are essentially told to monitor and return for follow-up, with little guidance on what to do during this critical window.

At each stage of this journey, families are making consequential decisions about finances, legal planning, living arrangements, and care - often without expert guidance. The person experiencing changes may still have capacity for important planning conversations, but families don't know how to have them. Early interventions could potentially slow decline, but families don't know what to prioritize.

And throughout this entire multi-year journey, someone is coordinating. Someone is noticing. Someone is researching. Someone is worrying. Someone is managing the family's response.

That someone deserves support.

What It Means to Build Services for the Actual Coordinator

Recognizing who's really coordinating cognitive care has profound implications for how we design services:

Messaging that validates their experience. "You're not overreacting. You're not imagining it. The changes you're seeing are real, and you deserve expert guidance to navigate them."

Services that support the coordinator, not just the patient. This means recognizing that the wife who's compensating for her husband's memory lapses needs strategies for doing so sustainably. The daughter coordinating from three states away needs clear information to make decisions remotely. The adult children navigating sibling disagreements about their parent's care need frameworks for productive conversations.

Proactive rather than reactive care models. Instead of waiting for crisis or diagnosis, offering longitudinal monitoring and guidance during the years when families most need it - when they're noticing changes but the healthcare system says "not yet."

Acknowledging the invisible labor. The coordination work is real work. It takes time, emotional energy, and often comes at the cost of careers, relationships, and personal wellbeing. Services should recognize this reality rather than treating it as incidental to the "real" patient care.

Why Referral Partners Need to Know This

If you're a healthcare provider working with older adults, you've probably seen this dynamic play out:

A couple comes in for medical care. The wife makes the appointment. She's the one asking the questions. She's noticed changes in her husband's thinking and judgment. She wants to know more "just in case."

Or an adult daughter schedules a consultation about her mother's finances. She's noticed confusion about bills, unusual purchases, vulnerability to scams. She's trying to figure out how to join the decision-making process while preserving her mother's dignity and autonomy. This is the shared decision-making threshold.

The person sitting across from you asking these questions? That's your actual client for cognitive health services.

When you're considering referrals for families with cognitive concerns, ask yourself: Who initiated this conversation? Who's been doing the research? Who will be implementing the recommendations?

That's who needs to know about services designed for family coordinators navigating cognitive change.

To the Family Coordinators Reading This

If you're the daughter who took a day off work to bring your father to appointments...

If you're the wife who's been quietly compensating for your husband's memory lapses...

If you're the adult child trying to coordinate care from three states away...

If you're the one who's been Googling "early signs of dementia" and asking AI if you're overreacting...

You're not overreacting. The changes you're noticing are real.

You're not alone in carrying this burden. This is a pattern across millions of families.

And you deserve support that recognizes the work you're actually doing.

The healthcare system wasn't designed for the role you have. But we can redesign the experience to serve the people navigating cognitive uncertainty - not just the patients, but the families, and specifically the women who disproportionately carry the coordination burden.

That's what I'm building with Treasure Coast Cognition's Cognitive Stewardship model: Longitudinal support throughout the multi-year journey from first concerns through diagnosis and beyond, recognizing that families - and particularly family coordinators - need expert guidance to navigate cognitive change with dignity, agency, and clarity.

The question "Who's really coordinating cognitive care?" isn't just an observation about gender dynamics in healthcare (men are caregivers, too).

It's a question we should ask before we design the services that help those coordinating cognitive care.