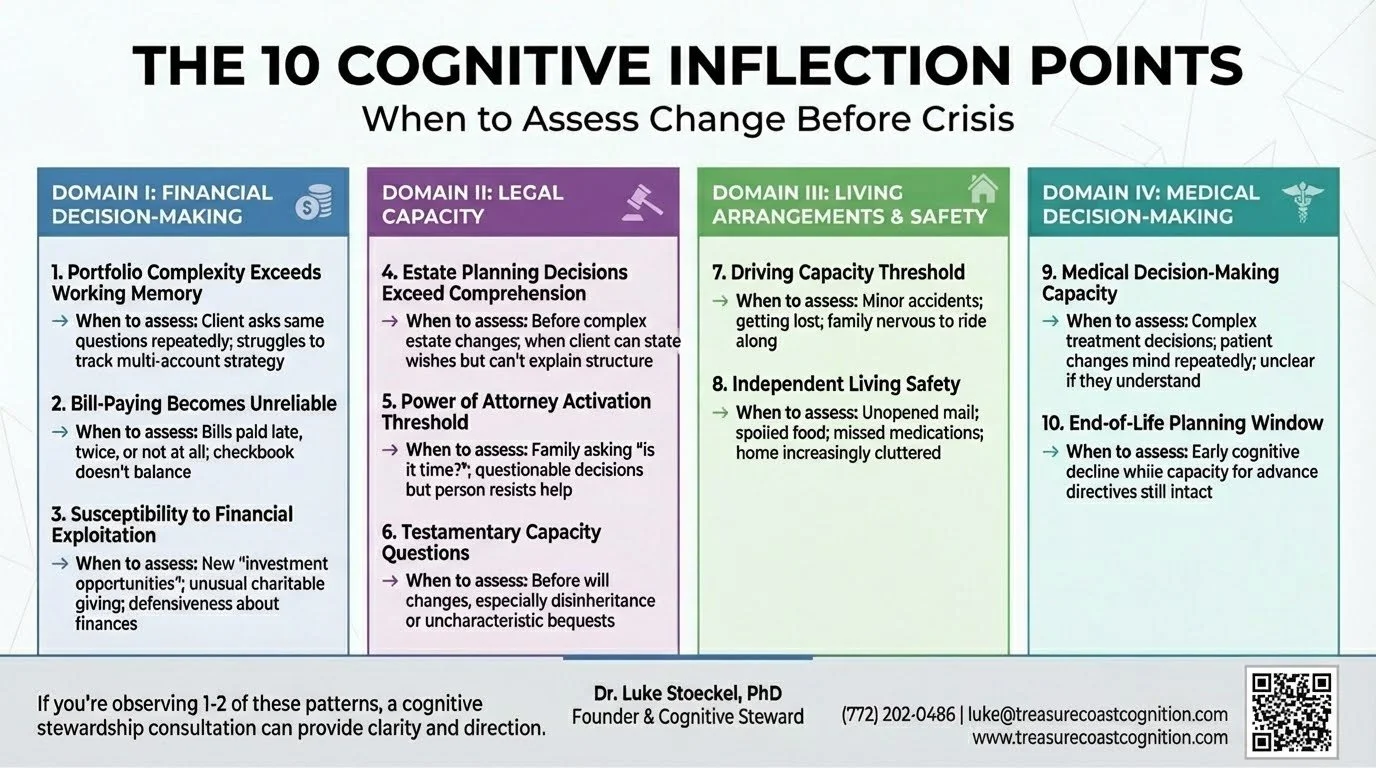

An inflection point is a moment when a relatively small cognitive change creates disproportionate risk for poor outcomes.

These aren't binary thresholds where capacity suddenly disappears. They're gradient transitions where specific cognitive functions decline in ways that impact specific real-world decisions.

The framework identifies 10 predictable decision points that most families encounter during cognitive transitions. If you recognize them early, proactive planning is still possible. If you miss the window, you're managing crisis.

Here's what to watch for:

DOMAIN I: Financial Decision-Making

1. Portfolio Complexity Exceeds Working Memory

What to watch for:

Difficulty tracking multiple accounts

Conversations with advisors require more repetition

Struggling to synthesize overall investment strategy

Increasing reliance on written summaries

The cognitive change: Working memory decline—difficulty holding and manipulating multiple pieces of information simultaneously

Why it matters: The person may still be able to discuss individual investments, but complex portfolio rebalancing, tax strategy, and multi-year planning may exceed current capacity. Without recognition of this change, they may agree to strategies they don't fully understand or resist necessary changes because they can't track the reasoning.

The decision point: Should we simplify the portfolio to match current capacity, or add oversight while maintaining complexity?

2. Bill-Paying Becomes Unreliable

What to watch for:

Bills paid late, twice, or not at all

Checkbook doesn't balance

Confusion about automatic payments

Insistence they paid something they didn't

The cognitive change: Executive function and prospective memory decline—difficulty remembering to perform future tasks and monitoring what's been completed

Why it matters: Bill-paying errors are often among the first visible signs that cognitive changes are affecting instrumental activities of daily living. Late payments can damage credit scores, duplicate payments drain accounts, and unpaid bills create legal consequences. More importantly, if bill-paying is compromised, more complex financial management is almost certainly at risk.

The decision point: Is this occasional forgetfulness that can be addressed with organizational systems, or is this evidence of declining capacity that requires direct oversight?

3. Susceptibility to Financial Exploitation

What to watch for:

Sudden interest in questionable "investment opportunities"

Difficulty ending sales calls

Charitable giving disproportionate to values or means

New "advisors" the family hasn't met

Defensiveness when questioned about financial decisions

The cognitive change: Decline in judgment, emotional regulation, and social cognition—particularly the ability to detect deception, assess risk, and resist persuasion

Why it matters: Elder financial exploitation is estimated to cost older adults billions of dollars annually, with individual losses often averaging $120,000. Once exploitation begins, it tends to escalate. Victims are often too embarrassed to report it, and by the time family members discover it, significant assets may be gone.

The decision point: Can they still manage financial relationships independently, or do they need protective oversight while preserving as much autonomy as possible?

DOMAIN II: Health & Medical Decision-Making

4. Medication Management Becomes Unreliable

What to watch for:

Medications taken at wrong times or in wrong doses

Pills remaining in organizers days after they should have been taken

Confusion about which medication treats which condition

Duplicate or missed doses

The cognitive change: Executive function and prospective memory decline affecting the ability to follow complex medication regimens

Why it matters: Medication non-adherence is associated with increased hospitalizations, disease progression, and preventable complications. For conditions like hypertension, diabetes, or heart disease, inconsistent medication use creates serious health risks. It's also an early indicator that other complex health management tasks may be compromised.

The decision point: Can medication management be maintained with organizational systems and reminders, or is direct oversight required?

5. Complex Medical Decisions Exceed Comprehension

What to watch for:

Struggling to weigh treatment trade-offs

Asking appropriate questions but difficulty retaining information

Changing mind repeatedly about treatment preferences

Physician uncertain whether they truly understand implications

The cognitive change: Decline in complex reasoning, future orientation, and ability to weigh probabilistic outcomes

Why it matters: Medical decision-making capacity is decision-specific and task-dependent. Someone might retain capacity for routine medical decisions but not for complex treatment choices involving risk/benefit analysis and uncertain outcomes. Without proper assessment, patients may make choices they don't fully understand, or family members may inappropriately override autonomous preferences.

The decision point: Can they make this specific medical decision independently, or is supported decision-making needed to ensure understanding?

6. Health Maintenance Tasks Decline

What to watch for:

Missed medical appointments

Laboratory work that doesn't get completed

Recommended screenings or follow-up visits falling through the cracks

Health conditions worsening due to lack of consistent management

The cognitive change: Executive function decline affecting planning, initiation, and follow-through on health maintenance activities

Why it matters: Preventive health care and chronic disease management require consistent execution of multi-step tasks—scheduling appointments, attending visits, following up on recommendations, and coordinating between providers. When executive function declines, these tasks can fail even when the person intellectually "knows" they should do them.

The decision point: Can health maintenance be sustained with reminders and organizational support, or does someone need to take over coordination?

7. Advance Care Planning Window

What to watch for:

Early cognitive decline but still able to discuss future care preferences

The conversation keeps getting postponed because it's difficult

Window for autonomous decision-making gradually closing

The cognitive change: Capacity for advance care planning remains intact, but progressive decline is foreseeable

Why it matters: This represents the last opportunity for the person's own voice to meaningfully guide future medical care. Once capacity is lost, families must make decisions without clear guidance from the person, often leading to conflict, guilt, and choices that may not reflect the individual's values.

The decision point: Is this the appropriate time to document preferences while decision-making capacity is intact?

DOMAIN III: Living Arrangements & Safety

8. Driving Capacity Threshold

What to watch for:

Minor traffic incidents or fender-benders

Getting lost in familiar areas

Family members feeling anxious when riding along

Slower reaction times

Defensive reactions and insistence they're "fine" despite observable concerns

The cognitive change: Possible decline in processing speed, visual-spatial function, divided attention, reaction time, judgment, or executive function—all critical for safe driving

Why it matters: Driving represents independence and identity for most adults. Loss of driving privileges is often one of the most emotionally charged transitions in cognitive aging. Yet continuing to drive with significantly impaired capacity creates safety risks for the driver and others. This requires objective assessment, not family opinion or self-report alone.

The decision point: Can they still drive safely without restrictions? Do they need limitations (daylight only, familiar routes, limited radius)? Must they cease driving?

9. Independent Living Safety

What to watch for:

Unopened mail accumulating

Spoiled food in refrigerator

Missed medications

Home increasingly cluttered or unkempt

Basic home maintenance not occurring

Safety hazards developing

Insistence they're managing fine despite visible evidence to the contrary

The cognitive change: Executive function decline affecting initiation, planning, and organization of daily tasks

Why it matters: This is the inflection point where "aging in place" transitions from preference to potential safety risk. Concerns include fall risk, medication errors, nutritional deficits, fire hazards, and vulnerability to exploitation. However, moving someone from their home prematurely can accelerate cognitive and functional decline and significantly impact quality of life.

The decision point: Can safety be maintained at home with appropriate supports, or has capacity declined to the point where a more structured living environment is necessary?

10. Social Isolation and Support System Erosion

What to watch for:

Decreasing engagement with friends and community

Not returning phone calls

Declining social invitations

Forgetting social commitments

Informal support network no longer in place

The cognitive change: Executive function and social cognition changes that make maintaining relationships more effortful, combined with reduced initiation and follow-through

Why it matters: Research indicates that social isolation is associated with accelerated cognitive decline, increased vulnerability to exploitation, and loss of the informal safety net that often identifies problems early. Without regular social contact, dangerous situations can develop undetected. Isolation may also increase dependence on whatever limited relationships remain—potentially increasing exploitation risk.

The decision point: Is the current level of social engagement adequate for safety and well-being, or does structured social support need to be introduced?

What to Do With This Framework

For Families

If you're noticing changes and wondering "is this normal aging or something more?"—that awareness is important.

Don't wait for crisis. Don't wait for formal diagnosis.

Consider these questions:

Is your parent managing finances and medications reliably?

Are health decisions becoming difficult to navigate independently?

Is driving safety becoming a concern?

Is independent living creating safety risks?

Is their support system diminishing?

If you're observing difficulties in 1-2 of these areas, it may be appropriate to seek professional assessment.

For Physicians

Routine brief cognitive screening can detect dementia but doesn't assess functional capacity for specific real-world decisions.

When patients are facing major medical or financial decisions, or when you observe functional decline in health management despite normal screening results, consider referral for comprehensive assessment including decision-specific capacity.

For Wealth Advisors

When you observe:

Portfolio management discussions requiring more repetition than previously

Uncharacteristic investment decisions

Difficulty tracking multiple accounts that were previously well-managed

Increased reliance on your recommendations without apparent understanding

Family members expressing concerns

Consider: Does my client's current cognitive capacity match the complexity of their portfolio and financial decision-making requirements?

From Reactive to Proactive

The traditional approach to cognitive aging is reactive: wait for crisis or formal diagnosis, then respond.

The 10 Cognitive Inflection Points framework enables proactive stewardship: identify specific decision points when comprehensive assessment should inform planning, intervene before crisis occurs, and navigate transitions strategically while preserving autonomy.

This framework serves:

Families - by transforming vague worry into specific, observable indicators and actionable steps

Physicians - by connecting brief cognitive screening to functional decision-making capacity assessment

Wealth advisors - by matching portfolio complexity to client cognitive capacity and identifying when oversight may be needed

The individuals themselves - by preserving autonomy where capacity exists while providing appropriate protection where capacity is declining

What Cognitive Stewardship Provides

Think of it as proactive planning for cognitive health, analogous to how you might work with a financial advisor for wealth management.

Just as you wouldn't wait until a financial crisis to plan for retirement, proactive planning for cognitive changes can prevent crises while preserving quality of life.

Comprehensive Assessment

Understanding current cognitive strengths and areas of change

Identifying which decisions can be made independently and which may need support

Establishing documented baseline for future comparison

Strategic Planning

Creating a roadmap informed by likely trajectory

Preserving independence and autonomy while addressing identified risks

Developing a proactive plan rather than crisis-driven reactions

Ongoing Professional Partnership

Regular monitoring as cognitive capacity evolves

Adjusting interventions and supports before crises develop

Expert guidance through one of life's most challenging transitions

The Bottom Line

Cognitive Stewardship is not about "taking over" or removing autonomy.

It's about providing clear information and strategic guidance so families can make informed decisions together while respecting the individual's remaining capacity and preferences.

If you're observing difficulties in 1-2 of these areas, you may be in the window where proactive planning can still make a meaningful difference.

Ready to learn more?

Schedule a complimentary consultation to discuss what you're noticing and whether comprehensive assessment and cognitive stewardship planning might be appropriate for your family.

Treasure Coast Cognition

Luke Stoeckel, PhD

Licensed Clinical Neuropsychologist

📞 (772) 202-0486

✉️ luke@treasurecoastcognition.com

🌐 www.treasurecoastcognition.com

Serving families in Vero Beach and throughout Florida's Treasure Coast

© 2025 Treasure Coast Cognition LLC. All rights reserved.