Why I'm Leaving My Office To Come To You

The most important part of a cognitive evaluation doesn't happen in my office.

It happens in your kitchen. Your bathroom. Your bedroom. The places where you actually live.

Because here's what I've learned after 20+ years of neuropsychological assessments: People can look fine in a clinic and be falling apart at home.

Your father aces the memory test in my office—but at home, there are 14 half-empty water bottles lined up on his dresser because he forgets he already got one.

Your mother seems oriented and alert during our appointment—but when I visit her home, the stove has scorch marks and expired food fills the refrigerator.

If I'm not seeing how you function where you live, I'm missing the whole story.

I was explaining Cognitive Stewardship to a physician friend in Vero over coffee. He listened as I described the model. Then he said: "This needs to be part of a new model for primary care. In-home primary care." I paused. "Tell me more."

Patients cycle through the hospital. Elderly, cognitively impaired, medically complex. Dehydration. UTIs that become delirium. Medication errors. Falls. The family doesn't realize it was this bad. And it’s preventable.

The problem isn't that primary care doctors don't care. It's that they can't see what's happening at home. Fifteen-minute office visits don't capture reality. When families arrive at the hospital, it’s to manage a crisis that's been building for months.

We need to go to you.

I come home, open my browser, and a new JAMA Network Open study appears showing primary care can spot early signs of dementia. This randomized clinical trial, led by Dr. Malaz Boustani and colleagues at Indiana University, tested a simple idea:

Can primary care clinics detect early cognitive decline using digital tools that fit into everyday workflows? Yes.

The study compared three approaches across nine federally qualified health centers in Indianapolis:

Usual care (no routine cognitive screening)

A machine-learning Passive Digital Marker (PDM) that analyzed existing electronic health record data to flag patients at risk

A PDM + patient-reported QDRS (Quick Dementia Rating System) combined approach

After one year, the combined approach led to 31% more new diagnoses of Alzheimer's disease and related dementias (15.4% vs 12.4% in usual care). Clinicians also ordered more appropriate diagnostic workups—brain imaging, labs, neuropsychological testing.

The key finding: Primary care can implement early cognitive screening at scale without disrupting workflow or adding clinician burden—and it helps identify people who would otherwise be missed.

Detection Isn't Prevention

But here's the piece we still haven't solved:

Detecting early cognitive changes is helpful—but it doesn't automatically lead to better outcomes for patients or families.

Finding early drift in memory, thinking, or executive function is only meaningful if we can do something with that information.

The limits of the study make this clear:

It focused on diagnosis, not real-world functioning

It didn't track hospitalizations, readmissions, or ED visits

It didn't address medication complexity, sleep disruption, caregiver strain, or home safety

It didn't connect detection to interventions that stabilize people at home

The Real Problems Happen at Home

People don't decline in the exam room.

They decline at home.

Long before a crisis or hospital visit, subtle destabilization shows up in:

Medication confusion (pills missed, duplicated, or taken incorrectly)

Sleep disruption (up all night, exhausted during day)

Mood and behavior changes (irritability, withdrawal, anxiety)

Executive function slips (bills unpaid, appointments forgotten)

Caregiver overwhelm (spouse exhausted, adult children burning out)

Missed follow-up appointments (patient forgets, family can't transport)

Mobility declines (unstable gait, near-falls, reduced activity)

Unsafe routines or environments (stoves left on, spoiled food, fall risks)

These changes are detectable. But right now, nobody is watching.

Early cognitive drift is rarely the sole cause of a readmission or major decline—it's the signal that bigger problems are coming.

By the time families seek help, the crisis has already arrived:

Dehydration → hospitalization

UTI → delirium → ED visit

Medication error → hypoglycemia → ambulance

Fall → hip fracture → surgery → skilled nursing facility

Caregiver collapse → emergency nursing home placement

Many of these crises are preventable.

What This Study Actually Tells Us

The JAMA article validates something important:

With the right tools, primary care can see the early drift.

The Passive Digital Marker (machine learning analyzing EHR patterns) plus the Quick Dementia Rating System (patient-reported symptoms) together changed clinician behavior—prompting diagnostic workup and earlier diagnosis.

We can detect cognitive changes in primary care.

Now we need to build the systems that respond before the drift becomes a crisis.

From Detection to Stabilization at Home

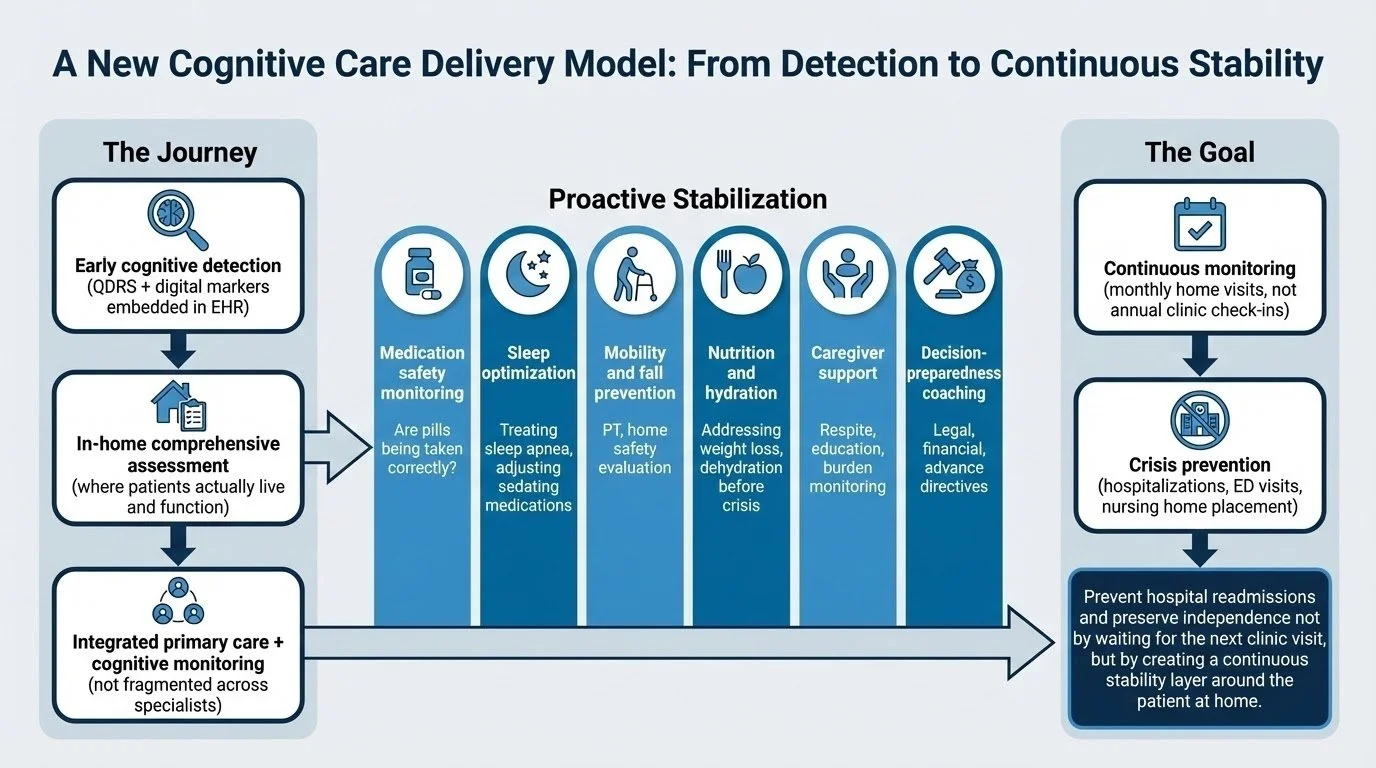

Imagine combining detection with a different care delivery model:

Early cognitive detection (QDRS + digital markers embedded in EHR)

↓

In-home comprehensive assessment (where patients actually live and function)

↓

Integrated primary care + cognitive monitoring (not fragmented across specialists)

↓

Proactive stabilization:

Medication safety monitoring (are pills being taken correctly?)

Sleep optimization (treating sleep apnea, adjusting sedating medications)

Mobility and fall prevention (PT, home safety evaluation)

Nutrition and hydration (addressing weight loss, dehydration before crisis)

Caregiver support (respite, education, burden monitoring)

Decision-preparedness coaching (legal, financial, advance directives)

↓

Continuous monitoring (monthly home visits, not annual clinic check-ins)

↓

Crisis prevention (hospitalizations, ED visits, nursing home placement)

Prevent hospital readmissions and preserve independence not by waiting for the next clinic visit, but by creating a continuous stability layer around the patient at home.

In-Home Primary Care

Traditional office-based primary care is not set up for cognitive change:

Transportation barriers if driving becomes risky or people refuse to visit the clinic

Clinic performance ≠ home performance: Someone may seem fine in a structured 15-minute clinic visit, but they may look very different at home

Medication management invisible: Pill bottles in clinic don't reveal whether pills are being taken correctly

Reactive, not proactive: Patient presents when crisis occurs; no monitoring between visits

Family excluded: Caregivers can't attend every appointment; clinician doesn't see family dynamics

In-home primary care solves these problems:

Direct observation: See how people actually function in their environment

Medication reality check: Pills scattered on counter, organizer filled incorrectly, expired meds not discarded

Home safety assessment: Loose rugs, clutter, spoiled food, burners on

Caregiver assessment: visible exhaustion, adult daughter on verge of quitting job

Early intervention: Detect problems before crises (dehydration, UTI, medication errors, fall risk)

Continuous relationship: Monthly visits create trust; patients more likely to report problems early

When you combine digital cognitive detection with in-home primary care delivery, you create a powerful prevention model:

Early detection identifies patients at risk

Home-based assessment reveals functional realities invisible in clinic

Integrated medical + cognitive management addresses complexity comprehensively

Continuous monitoring catches destabilization early

Proactive intervention prevents crises

Where Do We Go From Here?

Primary care can detect early cognitive decline.

Now we need to take the next step:

Build the systems that turn detection into prevention.

Extend monitoring from the clinic into the home where risk actually unfolds.

Create continuous stability around patients before crises force reactive management.

That's the work ahead.

My hospitalist friend was right. We need to go to them. We can detect the problems. Now we need to build the systems that prevent the crises—one home visit at a time.

Reference

Boustani MA, Ben Miled Z, Owora AH, et al. Digital Detection of Dementia in Primary Care: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(11):e2542222. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.42222