What Matters Most

Does a 0.45-point difference on a clinical scale matter?

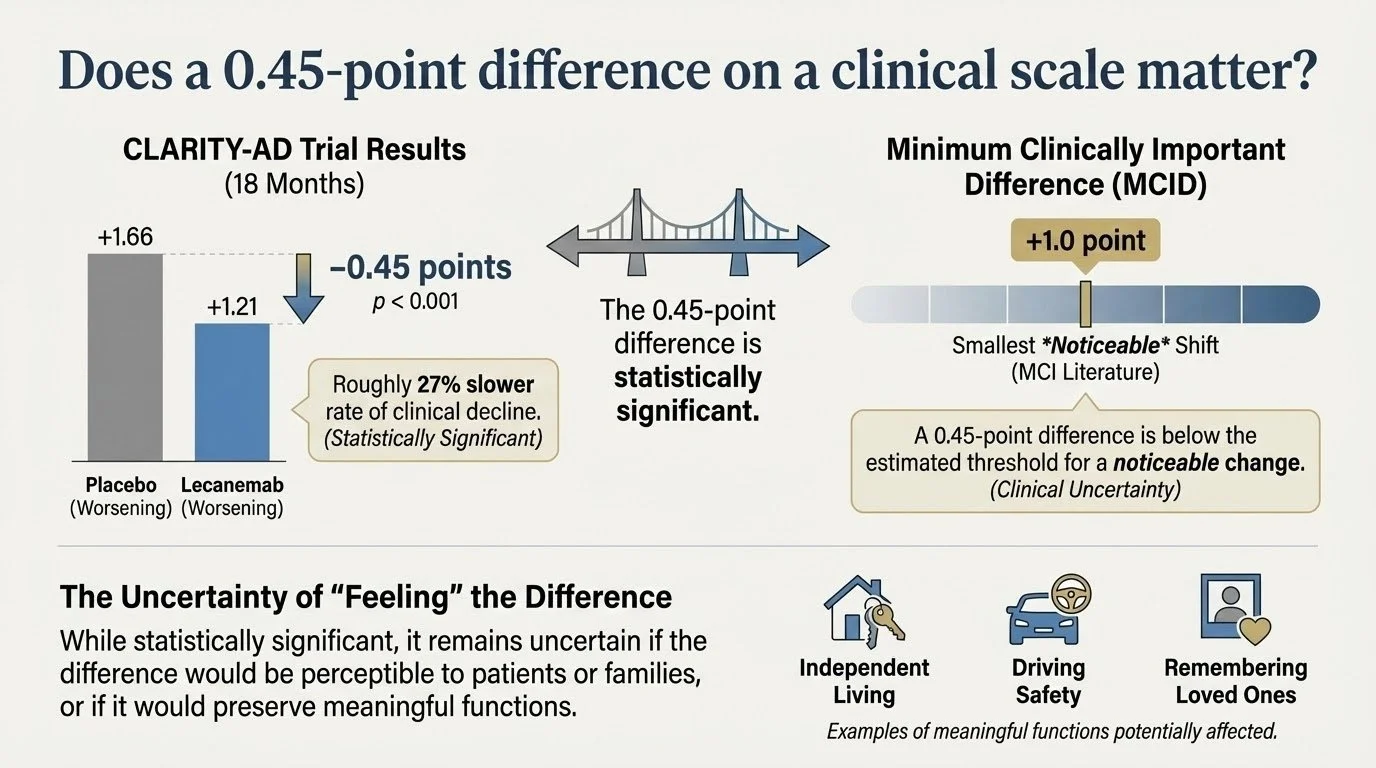

In the Phase 3 CLARITY-AD trial of lecanemab, patients with early Alzheimer’s disease treated with the drug had a mean change in CDR-SB of ≈ +1.21 at 18 months versus +1.66 on placebo (difference ≈ –0.45 points, p <0.001) — representing roughly a 27% slower rate of clinical decline.

Is a –0.45-point difference meaningful to a person or family? The minimum clinically important difference (MCID) literature suggests that, in MCI populations, a change of about +1 point on CDR-SB may represent the smallest shift likely to be noticeable.

In other words: while the result is statistically significant, it remains uncertain whether every individual would “feel” the difference, whether their family would observe it, or whether meaningful functions (e.g., independent living, driving safety, remembering loved ones) would be preserved.

Would this difference be noticeable in your daily life?

Would you feel different?

Would your family see a difference?

Would it preserve what you're terrified of losing?

The honest answer: We don't know.

What Clinical Trials Typically Measure:

CDR-Sum of Boxes scores (clinician ratings of thinking and function)

Amyloid plaque levels in the brain (measured by blood biomarkers and PET scans)

Cognitive test performance

Global clinical impression (clinician's rating of overall severity)

What Patients and Families Say Matters Most (in order):

Improving or restoring memory

Stopping disease progression

Slowing disease progression

Improving ability to do everyday tasks

Remembering family members

Remaining independent and not feeling like a burden

Removing plaques and tangles from the brain

Notice what's at the bottom? Removing amyloid plaques.

Notice what's missing entirely? The scales clinical trials use don't directly measure most of what patients care about: remembering loved ones' faces, not feeling like a burden, maintaining independence.

The 0.45-Point Question

Let's return to lecanemab's 0.45-point difference on the CDR-SB scale over 18 months.

Is 0.45 points meaningful?

The research community: Maybe. One expert panel suggested 0.5-1.0 points in a single domain (like memory) could be meaningful if caught early enough.

Patients and families: We don't know.

Does it mean:

Mom will remember my name for an extra 6 months?

Dad can balance his checkbook a bit longer?

My spouse won't need 24/7 care quite as soon?

I'll have more "good days" when I feel like myself?

These are the questions that matter and clinical trials typically don’t.

What "Clinically Meaningful" Should Mean

A 2025 workshop report proposed a new framework for defining meaningful outcomes in Alzheimer's trials:

1. Patient-Centered Outcomes Must Be Primary

Not secondary endpoints or exploratory analyses—primary. Trials should measure:

Patient-reported quality of life

Ability to perform activities that matter to the individual (hobbies, social engagement, self-care)

Caregiver burden and quality of life (disease affects the whole family)

Time to critical milestones (loss of independence, residential transition, loss of specific abilities)

2. "Minimal Clinically Important Difference" Must Reflect Patient Perspective

Currently, experts define thresholds like "1-2 CDR-SB points is meaningful." But meaningful to whom?

Better approach: Ask patients and families experiencing different levels of decline: "How much improvement or slowing would need to occur for you to consider treatment worthwhile given the risks, costs, and burdens?"

This is called anchoring to patient global impression of change—linking statistical measures to what people actually feel and notice.

3. Time Savings Must Be Interpretable

How many months of progression are delayed?

For example:

"Lecanemab provides approximately 5-7 months of delay in progression over 18 months of treatment"

"This means remaining at your current level of function about 5-7 months longer than you would without treatment"

This is interpretable. Patients can weigh: "Is 5-7 months of preserved function worth 18 months of infusions, MRI monitoring, risk of brain swelling, and cost?"

Different people will answer differently—and that's okay. The point is informed decision-making based on outcomes that matter.

Long-Term Economic Value

Modeling shows that even modest slowing of decline creates long-term value:

Scenario 1: 18 months of lecanemab, 27% slowing

Increased lifetime quality-adjusted life years (QALYs)

Reduced informal caregiving hours

Medical cost savings from delaying severe dementia stage

Net value: ~$40,000-60,000 per patient over lifetime

Scenario 2: 48 months of treatment, 50% slowing (hypothetical future treatment)

Dramatically increased QALYs

Years of delayed nursing home placement

Preserved workforce participation for both patient and caregiver

Net value: ~$150,000-200,000 per patient over lifetime

The insight: Even small effects compound over time. A 25% slowing may not seem dramatic year-to-year, but over 5-10 years could mean:

1-2 extra years living at home vs. nursing facility

1-2 extra years employed (for early-onset patients)

1-2 extra years when family caregivers don't need to quit jobs

Delayed transition to 24/7 care needs

But these benefits aren't captured in 18-month trials measuring CDR-SB scores.

People Are Complex

Research establishing Alzheimer's biomarkers has largely been conducted in select populations.

The problem:

Biomarkers (amyloid, tau) may be less strongly associated with cognitive decline in some people

Why? Likely because other factors contribute more to cognitive impairment:

Vascular disease from uncontrolled hypertension and diabetes

Social determinants of health (education quality, socioeconomic status)

Mixed pathologies (not pure Alzheimer's but combined pathologies)

Translation: What's "clinically meaningful" may differ depending on the person.

What This Means for Cognitive Stewardship

1. We Must Ask What Matters to YOU

In initial consultations, I ask:

What abilities are you most afraid of losing?

What would "success" look like for a treatment?

What trade-offs are you willing to accept (burden, cost, risk) for how much benefit?

What defines quality of life for you right now?

These answers guide everything: Whether to pursue treatments, which risk factors and lifestyle interventions to prioritize and how aggressive you should be, when to initiate legal planning.

2. We Must Measure What Matters

In addition to cognition, Cognitive Stewardship measures:

Functional capacity across domains (financial, medication management, driving, meal preparation)—the IADLs that patients prioritize

Patient-reported quality of life and sense of well-being

Care partner burden and family impact

Preservation of meaningful activities (hobbies, social connections, independence)

Time to critical milestones (independent living, drive safely, manage finances)

Every 6 months, we assess: Are you maintaining the abilities that matter most to you? Is quality of life preserved? Is family coping?

This tells us whether interventions are working in ways that matter—not just whether CDR-SB changed by 0.5 points.

3. We Must Translate Science into Lived Experience

I don't tell patients: "Your CDR-SB score increased 1.5 points over the past year."

I say: "Your memory and problem-solving have declined to a level where managing finances independently is becoming risky. Last year, you could balance your checkbook and detect errors. Now, you're missing bills and making calculation mistakes. This suggests we should implement financial protections like joint account management and power of attorney activation."

I don't say: "Lecanemab slows decline by 0.45 CDR-SB points over 18 months."

I say: "Lecanemab might give you about 5-7 months longer at your current level of function—meaning abilities like driving, managing your home, and participating in hobbies might be preserved a bit longer. We'd need to weigh this modest benefit against biweekly infusions, brain swelling risk, and costs. What feels right to you?"

This is patient-centered communication—translating research findings into terms that enable informed decisions.

4. We Must Empower Patients with Their Own Data

The Study Participant Bill of Rights says patients deserve their research results. Cognitive Stewardship goes further: You deserve results explained in context, with action plans, and with continuity of expertise.

You're not a data point. You're a partner in managing your cognitive health.

The Bottom Line: Ask the Right Questions

The next time you read a headline about an Alzheimer's drug showing "statistically significant benefit," ask:

Benefit for what outcome?

Meaningful to whom?

How would this feel in daily life?

Is this what patients and families are hoping for?

The 0.45-point CDR-SB difference isn't inherently meaningful or meaningless. Context makes it meaningful:

To a 68-year-old woman terrified of forgetting her grandchildren, 5-7 months of preserved memory might be priceless—worth the infusions and risks.

To an 82-year-old man who values quality over quantity and hates medical procedures, modest slowing may not justify treatment burden.

Both are valid. The problem is we don't have the data to help people make truly informed choices aligned with their values.

Cognitive Stewardship fills the gap—measuring what matters, translating science into lived experience, and empowering you to make decisions aligned with your priorities.

References

van Dyck CH, Swanson CJ, Aisen P, et al. Lecanemab in Early Alzheimer's Disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(1):9-21. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2212948

Andrews JS, Desai U, Kirson NY, et al. Disease Severity and Minimal Clinically Important Differences in Clinical Outcome Assessments for Alzheimer's Disease Clinical Trials. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2019;5:354-363. doi:10.1016/j.trci.2019.06.005

Stoeckel LE, Fazio EM, Hardy KK, Kidwiler N, McLinden KA, Williams B. Clinically Meaningful Outcomes in Alzheimer's Disease and Alzheimer's Disease-Related Dementias Trials. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2025;11(1):e70058. doi:10.1002/trc2.70058