AI Can Help Interpret Your Health Data. That Is Not The Problem That Matters Most.

The new health tools from OpenAI and Anthropic are impressive. They also may not address what matters most for families navigating cognitive change.

OpenAI and Anthropic—two of the biggest names in AI—have launched health products within days of each other. Both let you connect your medical records and get personalized health insights. The various AI chatbots and tools available are impressive, they feel different, they have helped me do and understand things quickly and in new ways, but they have often convinced me of things that were not true, too.

This may remind some of us of the early WebMD and IBM Watson days. WebMD made health information accessible but didn't solve complex health decisions. IBM Watson promised AI-powered clinical intelligence but did not and was never accessible to regular people anyway. Now OpenAI and Anthropic have essentially combined both—AI-powered analysis that anyone can access.

Twenty years ago, WebMD was supposed to transform how we understood our health. And in many ways, it did—millions of people gained access to medical information that was previously locked away in textbooks and doctor's offices. It was a real improvement. It also didn't replace the need for doctors, didn't solve the problem of navigating complex health decisions, and didn't help families figure out what to actually do when facing something serious.

These new AI tools are more sophisticated than WebMD. They can synthesize your personal health data, translate medical jargon, and provide tailored responses. For many health questions, they'll be genuinely useful.

But if you're an adult child watching your parent struggle—wondering whether it's time to have the conversation about driving or finances, trying to coordinate care from a distance while family members disagree about what to do—you may find that these tools, like WebMD before them, don't quite address the problem you're actually facing.

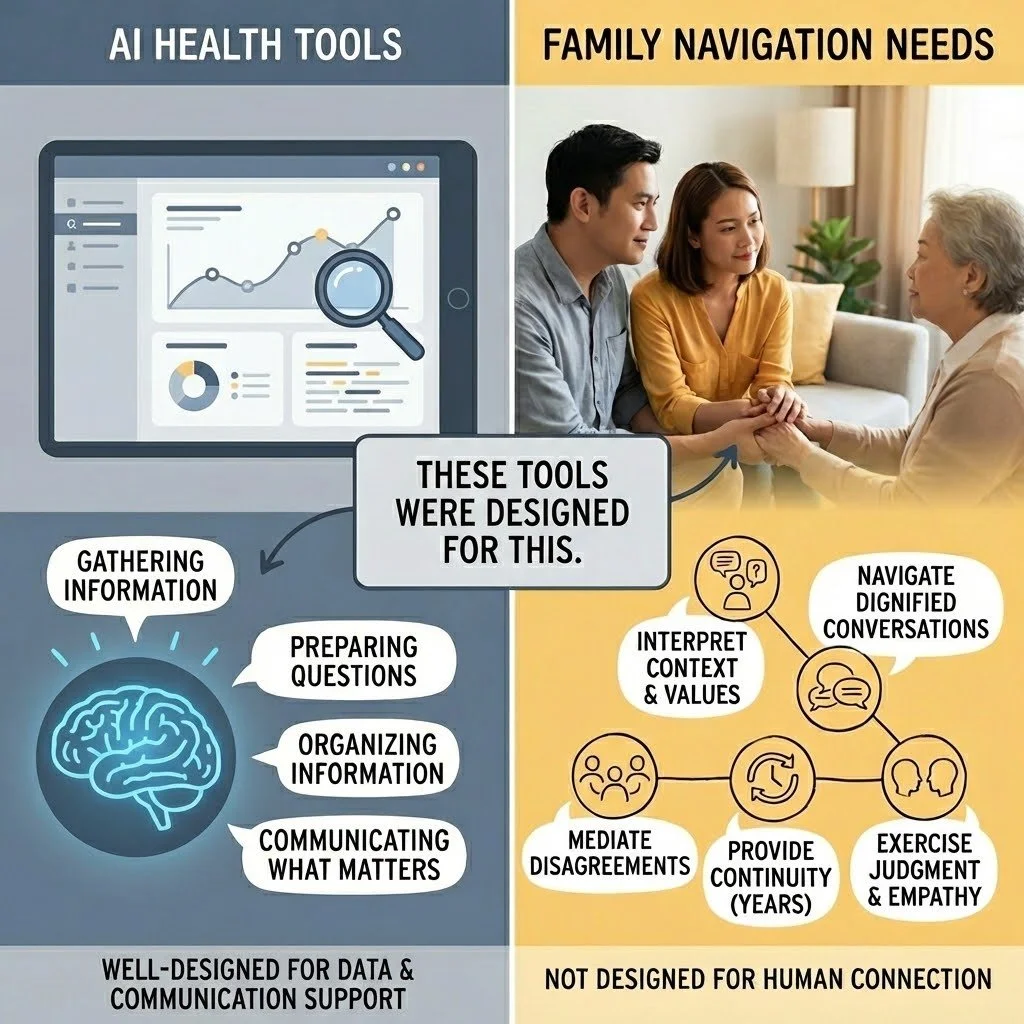

What These Tools Were Designed For

Let's start with what these tools do well, because they do some things very well.

They were designed to help individuals understand their own health data. They pull together lab results from multiple providers. They translate medical terminology into plain language. They can identify patterns across health metrics, test results, and clinical notes. They're available at 2am when you're worried about a test result.

OpenAI reports that 230 million people ask ChatGPT health questions every week. Anthropic's head of life sciences captured the appeal: "When navigating through health systems and health situations, you often have this feeling that you're sort of alone and that you're tying together all this data from all these sources."

That's a real problem, and for many people—particularly those managing their own health with full cognitive capacity—these tools offer a real solution. They were well-designed for that purpose.

The question is whether that purpose matches what families navigating cognitive change actually need.

What These Tools Weren't Designed For

These tools were built on certain assumptions. The user is managing their own health. The user can evaluate whether the information seems accurate. The user can take action on what they learn. The user has access to the relevant health data.

For families navigating cognitive change, those assumptions often don't hold.

The person who needs help may not recognize they need it. Cognitive decline often impairs insight—a phenomenon clinicians call anosognosia. Your father may not notice the changes you're seeing, or he may be frightened and expressing that fear as anger when you raise concerns. AI can synthesize his medical records. It wasn't designed to help you navigate a conversation with someone who doesn't believe anything is wrong. The models weren’t trained on anosognosia data and I have not seen research that shows the models perform well in clinical cases involving social interaction when one partner has limited insight.

You may not have access to the data. These tools assume you're connecting your Apple Health, your patient portal, your lab results. But you're trying to help someone else—someone who hasn't given you access (or not full access), who may not remember their passwords, whose medical information you might legally be unable to see. Medical records often don’t even include the data that matters most for managing care decisions. Can you get an answer? Yes. Is that answer accurate? Unclear. Is that answer helpful? Unclear. Is that answer harmful? Unclear.

Family decisions aren't individual decisions. Your brother thinks you're overreacting. Your sister thinks Mom should be in a facility. You're trying to coordinate care while managing everyone's emotions, your own guilt, and a lifetime of family dynamics. These tools were designed for one person asking about their own health, not for the complexity of family decision-making.

Information wasn't the bottleneck. You've probably already Googled more than you wanted to know about cognitive decline. You've read the Alzheimer's Association materials. You may have a folder of articles about power of attorney and warning signs. The information exists. What you need is help figuring out what it means for your family and what to actually do about it.

What the Data Can't Tell You

AI health tools are only as good as the data they're trained on and the data they can access. Both have significant limitations for families navigating cognitive change.

Training data reflects healthcare's existing patterns. These models learned from existing medical records, research studies, and health information. If the healthcare system has historically under-diagnosed cognitive decline in certain populations, dismissed family concerns, or failed to document early warning signs, AI trained on that data will inherit those blind spots. The models are excellent at pattern recognition—but they can only recognize patterns that exist in their training data.

Medical records capture what gets documented, not what's happening. Your mother's medical record shows her last visit was "unremarkable." It doesn't capture that she's been hiding unpaid bills for six months, that she gave $5,000 to a phone scammer last week, or that she no longer recognizes her grandchildren's names. AI can only access the slice of reality shared with it.

Some populations are systematically underrepresented. A widely-cited study found that a common healthcare algorithm underestimated the health needs of Black patients by using prior healthcare spending as a proxy—encoding historical inequities into automated recommendations. When certain communities are underrepresented in training data, AI tools may work less well for exactly the populations that already face barriers to care.

Rural, older, and less digitally-connected populations may be excluded entirely. Nearly 30% of rural adults lack access to AI-enhanced healthcare tools. Adults over 75 are most likely to struggle with digital interfaces and most concerned about data privacy. The people most likely to be navigating cognitive changes are often least able to benefit from these technologies.

What Families Actually Face

Here's what I've learned about what families are actually navigating:

The conversations are harder than the information. Knowing your father's executive function has declined is one thing. Telling him he shouldn't manage the family finances anymore—without destroying your relationship—is something else entirely. These conversations require timing, judgment, and deep knowledge of family dynamics that no tool can provide.

The medical system often doesn't help until there's a crisis. You've mentioned your concerns to doctors. They did a brief cognitive screen, said "normal for age," and moved on. Meanwhile, you're watching someone make increasingly risky decisions and no one seems to take it seriously. AI tools that connect to medical records from those same dismissive appointments don't change this dynamic. AI tools that don’t have the information that matters most cannot integrate that information into guidance and care.

Caregiving is relentless and invisible. Caregiving is hard. The role demands constant vigilance, difficult decisions, and managing someone who may resent your help. Caregivers describe becoming "like a manager"—deciding everything on behalf of another person while that person often fails to understand why their autonomy is being taken away. This isn't an information problem. It's a human problem.

What you need changes over time. The questions you face in year one are different from year three or year seven. Decisions about healthcare, living arrangements, and finances unfold through ongoing negotiation within families. If the AI tool cannot accurately track those changes over time or treats each question in isolation or without full context, you may not get the guidance and support you need.

Where AI Fits—And Where It Doesn't

AI tools have been incredibly useful in some aspects of my work. They're useful for organizing information, troubleshooting, idea generation and testing, drafting documents, and surfacing patterns across work tasks and items. They help me like a clinical or research assistant I can bother at 2am. I see AI health tools serving a useful purpose in the future if all the risks and concerns are adequately addressed and if people want to use these tools. They may help surface data earlier, prepare better questions for appointments, and reduce some information-gathering burden.

But I see major gaps for what families navigating cognitive change most need:

Interpret data in the context of a specific family's situation, values, and dynamics

Navigate the conversations that preserve dignity while acknowledging hard truths

Mediate disagreements between family members with different perspectives

Provide continuity over a journey that spans years, not queries

Exercise judgment about when to push, when to wait, and what this particular family can actually live with

This isn't a criticism of AI. These tools were well-designed for what they were designed for. They just weren't designed for this.

The Trust Question

Only 5% of Americans say they trust AI "a lot" for health decisions. Trust in AI health information is actually declining—30% now express distrust, up from 23% two years ago. Most people still view their doctor as the most trusted source. It is less clear how people will view their doctors when they partner with AI to provide care.

That skepticism may be healthy. These tools are new. They haven't yet demonstrated reliability in high-stakes, complex family situations. For families facing cognitive decline—where the stakes involve autonomy, dignity, safety, and relationships that span decades—caution seems appropriate.

The question isn't whether AI is good or bad. It's whether these particular tools, designed for these particular purposes, address what families actually need. That families and providers understand the risks and that families and providers know how to use the tools to deliver the most benefit for what matters most to families. This means adequately accounting for biases in the training data, models, and risks that come with turning over aspects of care to a new technology.

This isn't about AI competing with doctors or AI being forced on providers and families. It's about filling a gap that neither fills: helping families interpret what's happening in context, navigate the conversations that matter, and make decisions they can live with over the years this unfolds. The stakes are high to do this in the right way centering the families that are navigating these changes together.