What Changes Brain Health vs. What Changes Alzheimer’s

If you've read about Alzheimer's disease, you've probably encountered two contradictory messages.

The first: Do these ten things and you can prevent Alzheimer's.

The second: There's nothing you can do — and the drugs don't really work anyway.

As with most false dichotomies, both are wrong. And the confusion between them causes real harm — leading families toward either false hope or premature resignation, neither of which serves them.

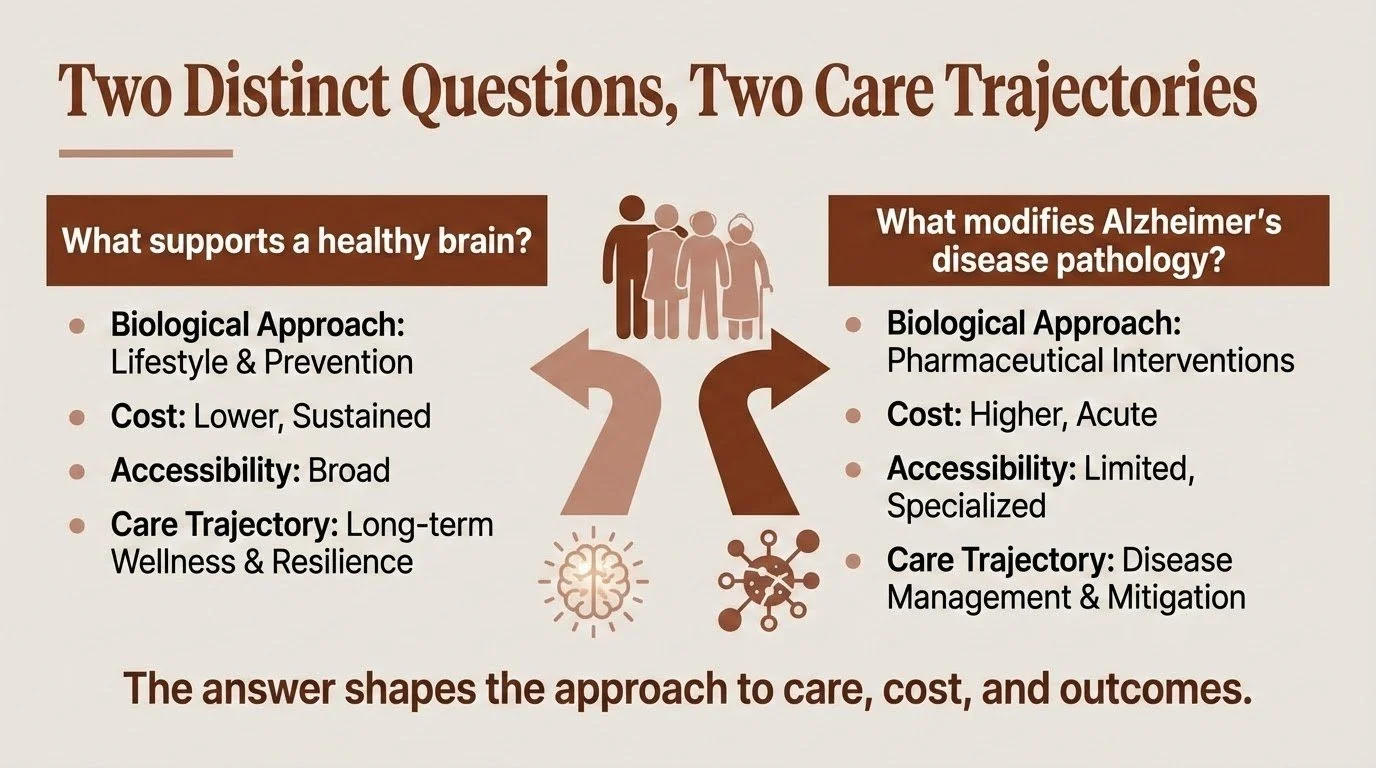

The problem is that most conversations about brain health blur together two fundamentally different questions:

What supports a healthy brain?

and

What modifies Alzheimer's disease pathology?

These aren't the same question. They differ not only in biological approach but also in cost, accessibility, and what they can realistically deliver. Understanding why — and what that means for you and your family — is one of the most important things I can help clarify.

Brain Health: Building Resilience

When researchers talk about lifestyle factors and brain health, they're describing something real and evidence-based. Regular physical exercise, quality sleep, cognitive engagement, social connection, managing vascular risk factors — these work.

At a 2019 National Academies workshop on brain health, I proposed a working definition of resilience that captures what we're actually building: A resilient person has a variety of neurocognitive tools and networks that can be activated in response to challenges, and can adaptively deploy these tools to optimize function when facing environmental and psychological demands. The Collaboratory on Research Definitions for Reserve and Resilience in Cognitive Aging and Dementia has developed consensus definitions distinguishing cognitive reserve, brain maintenance, and brain reserve — with resilience as an overarching framework. Resilience isn't about preventing damage — it's about having options when damage occurs.

The evidence for building resilience is solid. Large trials like FINGER and POINTER have demonstrated improvements in cognitive performance and risk profiles through structured lifestyle interventions. We continue to learn how, including how cognitive reserve builds a more adaptable brain that can compensate longer when damage occurs; vascular health that ensures adequate blood flow; and reduced systemic and neuroinflammatory burden associated with slower decline.

But here's the crucial distinction: these interventions build resilience. They may delay the expression of symptoms. They reduce risk. What they don't do — at least not directly — is stop the molecular machinery of Alzheimer's disease itself.

Importantly, no one "fails" their way into Alzheimer's disease. Genetics and biology matter enormously, even when people do everything right. The lifestyle work is worth doing — but it's not a guarantee, and families shouldn't carry guilt when decline happens despite their best efforts.

And critically, these interventions are accessible. They don't require specialized facilities, insurance approval, or infusion centers. The cost is measured in effort and consistency, not dollars.

Disease Modification: Targeting the Pathology

Alzheimer's disease involves a specific pathological process — the accumulation of amyloid plaques and tau tangles that progressively damage brain tissue. For decades, researchers have worked to develop treatments that target this cascade directly.

The timeline of progress here is worth understanding, because much of what we can now measure and treat has emerged remarkably recently.

The biomarker revolution: Until the past few years, confirming Alzheimer's pathology required either invasive lumbar punctures for cerebrospinal fluid analysis or expensive PET imaging costing thousands of dollars with limited availability. That's changing rapidly. Blood-based biomarkers — particularly phosphorylated tau at position 217 (p-tau217) — can now detect Alzheimer's pathology with accuracy often approaching PET imaging in research cohorts. Studies show p-tau217 levels begin rising more than 20 years before symptom onset, providing an unprecedented window into what's happening biologically. These tests are becoming available commercially for around $200, though clinical standards for interpretation and follow-up are still evolving.

Detection enables better decisions — even when treatment options are limited. Knowing what you're facing allows for realistic planning, targeted monitoring, and informed choices about emerging therapies.

Disease-modifying therapies: Anti-amyloid antibodies like lecanemab (Leqembi) and donanemab (Kisunla) represent genuine scientific progress. They can reduce amyloid burden in the brain. Clinical trials have shown modest slowing of decline in people with early-stage disease — approximately 25-35% slowing of progression over 18 months.

But "modest" is the operative word. These are not cures. They don't reverse damage already done. Their effects, while statistically meaningful, translate to relatively small differences in day-to-day function over the study periods. Some individuals and families experience noticeable benefit; others experience none. And the treatments come with real risks — brain swelling (ARIA-E) and microbleeds (ARIA-H) requiring careful monitoring with regular MRIs.

A recent episode of the Penn Memory Center's Age of Aging podcast reviewed where things stand after the 2025 Clinical Trials on Alzheimer's Disease (CTAD) conference. The picture is nuanced: anti-amyloid therapies show consistent but modest effects, while hoped-for breakthroughs in other approaches — like GLP-1 medications — have so far disappointed.

Cost and accessibility: This is where disease modification diverges sharply from brain health approaches. Lecanemab costs approximately $26,500 per year; donanemab runs about $32,000. Medicare covers these drugs, but patients face significant out-of-pocket costs — roughly $5,000-6,600 annually after deductibles, plus costs for required monitoring MRIs and infusion visits. The treatments require biweekly (lecanemab) or monthly (donanemab) infusions at specialized centers, genetic testing for APOE status, and ongoing safety monitoring.

One recent improvement: the FDA approved a subcutaneous autoinjector formulation of lecanemab (Leqembi Iqlik) in late 2025 for maintenance dosing. After completing 18 months of IV infusions, patients can now switch to weekly at-home injections — a 15-second self-administered dose that eliminates ongoing infusion center visits. And a supplemental application for subcutaneous initiation treatment — which would allow patients to bypass the IV infusion phase entirely and start treatment at home — was completed in November 2025 and is currently under FDA review.

If approved, this would represent a meaningful shift in accessibility. But for now, many families — particularly those in rural areas or without supplemental insurance — still face significant barriers to starting treatment, regardless of clinical appropriateness.

What may be coming: The next generation of therapies aims to address current limitations. "Brain shuttle" technologies — bispecific antibodies engineered to cross the blood-brain barrier via transferrin receptor binding — show early promise for improving drug delivery while potentially reducing side effects. Roche's trontinemab, which uses this approach, has shown rapid amyloid clearance at lower doses with encouraging early safety data, including very low rates of ARIA-E. In early trials, 91% of participants on the higher dose became amyloid-negative within six months.

These results are early and focused on biomarker outcomes; whether this translates into meaningful clinical benefit remains to be seen. But the direction is promising — better delivery, broader brain distribution, and potentially improved safety profiles.

Why Both Matter — And Why the Distinction Matters More

Here's what I want families to hold:

Do the lifestyle work. It's not nothing. Building cognitive reserve, protecting vascular health, staying engaged — these create real protection. They may give you more good years, more functional capacity, more time. They're accessible to nearly everyone, regardless of insurance status or geography.

And understand that lifestyle isn't a cure. It doesn’t look like exercise or crossword puzzles alone will stop tau from spreading. These are different biological problems requiring different solutions.

Take disease-modifying options seriously — but realistically. For appropriate candidates, anti-amyloid therapies represent a genuine, if modest, advance. But they're expensive, require significant infrastructure, carry real risks, and deliver incremental rather than transformative benefit. They're one tool, not a solution.

The danger comes from conflating these approaches. Families who believe lifestyle alone prevents Alzheimer's may delay necessary planning or feel blindsided when decline happens despite doing "everything right." Families who pin all hope on medications may be devastated by modest results — or may dismiss the meaningful protection that lifestyle factors actually provide.

Neither position serves you.

What This Means for Your Family

People living with Alzheimer's consistently tell us two things matter most: being treated as whole people — not diagnoses — and having time to make decisions while their voice still counts. Biomarkers and treatments matter only insofar as they support those goals.

Navigating this territory requires holding complexity — understanding what's within your control, what isn't, and how to plan wisely for both. It means neither over-relying on prevention promises nor surrendering to fatalism. It means understanding that the science is advancing rapidly, that what we can measure and treat today was impossible five years ago, and that thoughtful engagement beats both wishful thinking and despair.

This is part of what I help families do: make sense of the science as it actually stands, understand what it means for their specific situation, and build a path forward that accounts for both what we know and what remains uncertain.