What Happens When the World Speeds Up and Our Brains Slow Down?

There's a moment most people over fifty recognize but can't quite name. You are having a meal with friends or family, and the conversation shifts faster than you can track. Or you're merging onto a busy road and the gap between the cars and open lane closes before you get there. Or you are installing a new app on your device or creating a new online account, and by the time you've absorbed step two, they're on step five.

Nothing is wrong with you. Your reasoning is intact. Your words are there. Your judgment is sound. You have more knowledge than ever. But it feels like you are losing a fraction of a second each day.

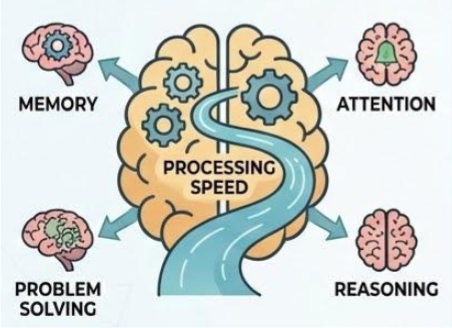

That something is processing speed — the rate at which your brain takes in information, makes sense of it, and produces a response. And understanding what happens when it changes is one of the most important things you can do for yourself or someone you love as you age.

Processing Speed

Processing speed isn't intelligence. It isn't memory. It isn't wisdom. It's the tempo of your thinking — how quickly your brain can manage and use information.

Think of it this way: if cognition is an orchestra, processing speed is the conductor's tempo. The musicians (your reasoning, your knowledge, your judgment) may be as talented as ever. But when the tempo slows, the whole performance changes. Some passages that require precise coordination start to fall apart. Some musicians can't finish their parts before the next section begins.

In 1996, Timothy Salthouse at Georgia Tech published what became the foundational theory of how processing speed relates to cognitive aging. His processing-speed theory proposed two mechanisms that explain why slower processing degrades cognitive performance, even when the underlying abilities are preserved (Salthouse, 1996, Psychological Review).

The first is the limited time mechanism. When processing is slow, you simply can't complete all the mental operations you need to within a given window. The conversation moves on. The traffic gap closes. The app tutorial leaves you behind. It's not that you can't understand — it's that the world doesn't wait.

The second is the simultaneity mechanism, and this one is more subtle. Many cognitive tasks require you to hold several pieces of information in mind at the same time — to see the relationships between them, to integrate them into a decision. But information doesn't stay active in your mind forever. It fades. And if your processing is slow, the early pieces of information may have already degraded by the time you've finished working through the later ones. You're trying to assemble a puzzle, but the first pieces keep dissolving before you can place the last ones.

Salthouse's insight was that these two mechanisms together can explain an enormous proportion of age-related cognitive change. In his studies, controlling statistically for processing speed eliminated roughly 75% or more of the age-related variance in measures of memory, reasoning, and spatial ability. That's a staggering number. It means that much of what we call "cognitive aging" isn't really about losing the ability to think — it's about losing the speed to think in a world that demands rapid coordination of information.

When Does Processing Speed Change?

Here's the part that surprises most people: processing speed starts declining in your late twenties.

That's not a typo. The research is remarkably consistent on this point. Fluid cognitive abilities — the ones that require you to process novel information, solve new problems, and respond quickly — begin a gradual, largely linear decline starting around age 25-30 and continuing throughout the lifespan. Change is imperceptible year to year but unmistakable decade to decade.

By contrast, crystallized abilities — your vocabulary, your accumulated knowledge, your expertise — continue to grow well into your sixties and seventies. This is why a sixty-year-old attorney may be a far better strategist than her thirty-year-old associate, even though the associate can process a new brief faster. The older attorney has seen more patterns, built deeper frameworks, and developed an intuitive sense for what matters. Her processing speed has slowed, but her wisdom — in the truest cognitive sense — has grown.

This divergence between crystallized and fluid abilities is one of the most important facts about cognitive aging. It means that as you age, you're not simply declining. You're changing shape. Some dimensions of your mind are shrinking while others are expanding. The question isn't whether you're getting "better" or "worse" at thinking. The question is: how do you reorganize your life to play to your strengths?

There Is More Than One Decline Curve

The story of cognitive aging is richer than a single curve heading downward.

Laura Germine is a cognitive scientist who co-created TestMyBrain.org, one of the first online cognitive testing platforms. Through that platform and others, Germine and her colleagues have collected cognitive data from millions of volunteers — an unprecedented scale that allowed them to map when different mental abilities actually peak across the entire lifespan.

Processing speed peaks early, as Salthouse predicted — around age 18 or 19. Short-term memory improves until about 25 and begins declining around 35. So far, consistent with the standard picture. But then things get interesting. Working memory climbs into the late 20s and early 30s and declines only slowly. Social cognition — the ability to read other people's emotions — peaks in the 40s and doesn't start to significantly decline until after 60. And vocabulary? It just keeps improving, all the way into the late 60s and early 70s.

In other words, there is no single peak for cognitive ability. Different capacities are on different timelines, and some are still developing well into midlife. Your brain at 55 or 65 or 75 or 85 isn't just a slower version of your brain at 25. It's a fundamentally different instrument — worse at some things, better at others, and still changing in ways that matter enormously for real-world functioning.

The World Got Faster Too

Here's what makes the processing speed story so much more urgent than it was when Salthouse published his theory in 1996: the world has changed at least as much as our brains have.

In 1996, most people got their news from a morning paper and an evening broadcast. Email was a novelty. The internet was a curiosity. There were no smartphones, no social media feeds, no push notifications, no algorithmic content streams designed to capture and hold your attention for as long as possible.

Today, the average person is inundated with messages throughout the day. Our phones buzz with notifications. Our inboxes fill faster than we can empty them. Medical information arrives not from a single trusted physician but from a firehose of Google results, patient portals, wellness apps, and well-meaning relatives forwarding articles. Financial information moves in real-time tickers. The news cycle runs 24 hours. Stores don’t close on Sundays.

This means that the challenge of cognitive aging isn't just that our brains are slowing down. It's that our brains are slowing down while the world is speeding up. These two curves — one biological, one technological and cultural — are moving in opposite directions, and the gap between them is widening every year.

And it's not just processing speed, our attention — the gateway through which all information must pass before it can be processed at all — is being reshaped by the world we've built.

Attention in an Age of Distraction

Attention isn't a single thing. Cognitive scientists distinguish between several forms: sustained attention (maintaining focus over time), selective attention (filtering relevant from irrelevant information), divided attention (managing multiple streams of information simultaneously), and attentional switching (shifting focus between tasks).

All of these are affected by aging, but the modern information environment puts particular strain on selective and divided attention — the very capacities that help you sort signal from noise and manage competing demands.

Consider what happens when you sit down to research a Medicare supplemental plan online. You need to compare coverage options across multiple providers, each with different terminology. Pop-up ads compete for your visual attention. Sponsored content is designed to look like legitimate information. Your email pings. A news alert flashes across your screen. Even a young person with peak processing speed would find this challenging. For someone whose processing speed has slowed and whose attentional filtering has become less efficient, it can be genuinely overwhelming.

The result is a kind of cognitive mismatch that didn't exist a generation ago. Our grandparents experienced age-related processing speed decline in a world that moved at the speed of handwritten letters, face-to-face conversations, and decisions that could unfold over weeks. We're experiencing it in a world that moves at the speed of fiber optics and expects responses in minutes.

When the information environment outpaces your ability to process it, you don't just miss things — you become dependent on others to filter, interpret, and act on information for you.

When Disease Accelerates the Clock

Normal aging produces a gradual, manageable slowing. But several diseases of aging can dramatically accelerate the process, creating challenges that require more deliberate adaptation.

Alzheimer's disease is the most well-known. While Alzheimer's is most associated with memory loss in the public imagination, slowed processing speed is one of the earliest and most consistent findings, often detectable years before a clinical diagnosis. In the preclinical window — what I think of as the "hidden window" — processing speed deficits begin to interact with the disease's effects on memory and executive function, creating a cascade that progressively undermines the person's ability to manage complex decisions.

Cerebrovascular disease — the accumulation of small-vessel damage in the brain from conditions like hypertension, diabetes, and atherosclerosis — may be an even more common driver of processing speed decline. White matter lesions, which show up as bright spots on brain MRI, disrupt the connections between brain regions, literally slowing the transmission of neural signals. This is one reason why managing cardiovascular risk factors (blood pressure, blood sugar, cholesterol) is one of the most evidence-based things you can do to protect your processing speed.

Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis, traumatic brain injury, and major depression all carry significant processing speed costs. In each case, the mechanisms may differ — dopamine depletion in Parkinson's, demyelination in MS, diffuse axonal injury in TBI, altered neural network efficiency in depression — but the experience is similar: the world feels like it's moving too fast.

The World Changes When The Clock Slows

When processing speed slows significantly — whether from normal aging, disease, or both — and the information environment continues to accelerate, the world doesn't just feel faster. It feels different. The change reshapes your daily experience in ways that are hard to articulate but impossible to ignore.

Conversations become harder to follow. Not because you don't understand the words, but because by the time you've fully processed one point, the speaker has moved on to the next. Group conversations are especially demanding because they require rapid tracking of multiple speakers, shifting topics, and social cues. Many people with slowed processing speed start to withdraw from social situations because the cognitive load of keeping up is exhausting.

Driving becomes riskier. Driving is one of the most processing-speed-dependent activities in daily life. It requires continuous integration of visual information from multiple sources, rapid decision-making, and split-second motor responses. Research using the Useful Field of View (UFOV) paradigm has consistently shown that slower processing speed predicts higher crash risk in older adults. This doesn't mean every older adult is an unsafe driver. It means that when processing speed drops below a certain threshold, the margins of safety narrow in ways that matter.

Financial decisions become vulnerable. Financial decisions — especially the complex, multi-step ones involving investments, estate planning, and major purchases — require exactly the kind of simultaneous information integration that Salthouse's simultaneity mechanism describes. You need to hold the terms of the deal in mind while comparing them to alternatives, while assessing risk, while considering tax implications. When processing speed slows, you may still understand each piece individually, but the ability to hold all the pieces together at once declines. This is when people become vulnerable to poor decisions, scams, and undue influence — not because they've lost their judgment, but because they can't deploy their judgment fast enough to catch the problems.

Technology becomes a barrier. Modern technology is designed by and for fast processors. Interfaces change rapidly, notifications demand immediate attention, and the default assumption is that users can keep up with multi-step, time-sensitive interactions. For someone with slowed processing speed, even routine tasks like online banking, telehealth appointments, or navigating a new phone update can become sources of frustration and avoidance.

Medical decision-making gets harder. Imagine sitting in a doctor's office, receiving a new diagnosis. The physician is explaining treatment options, each with its own risk-benefit profile. You're trying to process the diagnosis itself while simultaneously weighing the options. With slowed processing speed, you may leave the appointment feeling like you understood very little — not because the information was too complex for you, but because it was delivered too fast for your current processing capacity.

When Slower Can Be Better

People who process more slowly tend to be more deliberate. They're less likely to jump to conclusions. They're more likely to weigh evidence carefully before committing to a decision. In situations that reward caution and thoroughness over speed — and many of life's most important situations do — slower processing can actually be an asset.

Research on decision-making across the lifespan supports this. Older adults tend to rely more on gist-based reasoning, focusing on the essential meaning of information rather than getting lost in the details. They're often better at filtering out irrelevant information and zeroing in on what matters. This isn't a deficit — it's an adaptation, and in many contexts, it produces better outcomes.

The problem isn't that slower processing is inherently bad. The problem is that the world isn't designed for it. When you can restructure the environment to match the processor — giving yourself more time, reducing distractions, breaking complex decisions into smaller steps — the preserved reasoning and accumulated wisdom of aging can shine.

What the Evidence Says About Interventions

If processing speed is so central to cognitive aging, can anything be done about it? The answer, increasingly, is yes — with some important caveats.

The strongest evidence comes from the ACTIVE trial (Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Vital Elderly), the largest and longest randomized controlled trial of cognitive training in older adults. In a remarkable 20-year follow-up published just this month in Alzheimer's & Dementia: Translational Research and Clinical Interventions (Coe et al., 2026), researchers found that participants who completed speed-of-processing training — about five to six weeks of adaptive computer-based exercises — plus booster sessions one to three years later, had a 25% lower rate of dementia diagnosis over the next two decades compared to the control group.

This is extraordinary for several reasons. First, the intervention was modest: roughly ten sessions of 60-75 minutes each, followed by a few booster sessions. Second, neither memory training nor reasoning training produced the same effect — only speed training did. Third, the effect lasted twenty years. As Marilyn Albert, the corresponding author and director of the Johns Hopkins Alzheimer's Disease Research Center, noted, even small delays in the onset of dementia could have an enormous public health impact.

Why speed training and not the others? The researchers point to a key difference: speed training is adaptive (it gets harder as you improve) and it drives implicit learning — the kind of unconscious skill-building that resembles developing a reflex. Memory and reasoning training, by contrast, taught explicit strategies that everyone in the group learned the same way. Implicit learning engages different brain networks and may produce more durable neural changes.

Physical exercise is the other intervention with strong evidence for protecting processing speed. Aerobic exercise in particular has been linked to preserved white matter integrity, improved cerebrovascular health, and better processing speed performance in both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. The mechanisms are probably multiple: exercise improves blood flow to the brain, reduces inflammation, stimulates the release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and helps manage the cardiovascular risk factors that contribute to small-vessel disease.

Cardiovascular risk management — controlling hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia — protects the brain's white matter infrastructure and may be the single most impactful thing most people can do to preserve processing speed. The SPRINT-MIND trial showed that intensive blood pressure control (targeting systolic pressure below 120 mmHg) reduced the risk of mild cognitive impairment compared to standard treatment.

During sleep, the brain clears metabolic waste products, consolidates memories, and restores neural function. Chronic sleep deprivation and untreated sleep apnea are both associated with reduced processing speed and accelerated cognitive aging.

Adapting Your Life to a Changing Brain

The interventions above are about slowing the decline. But equally important — and often more immediately practical — is adapting your life to work with your changing brain rather than against it.

Here's what that looks like in practice:

Give yourself more time. This sounds obvious, but it requires a genuine restructuring of how you approach tasks. If you used to review financial documents the night before a meeting, start reviewing them three days before. If you used to make medical decisions in the appointment, start requesting information in advance so you can process it at your own pace.

Curate your information environment. This may be the most underappreciated adaptation available to you. Unsubscribe from email lists that create noise. Turn off non-essential notifications on your phone. Designate specific times for checking news rather than letting it wash over you all day. When you need to research something important — a medical decision, a financial product, a legal question — don't start with an open-ended Google search. Start by asking a trusted professional or knowledgeable person to point you to the two or three sources that actually matter. Your goal isn't to see everything. Your goal is to see the right things with enough time and focus to process them well.

Protect your attention like you protect your money. Every app, every platform, every notification is asking for a piece of your attention — and attention is a finite cognitive resource that becomes more precious as processing speed declines. Be as deliberate about where you spend your attention as you are about where you spend your dollars.

Reduce the need for simultaneous processing. Break complex decisions into sequential steps. Write things down. Use checklists. These aren't signs of weakness — they're intelligent adaptations to a known change in your cognitive profile.

Protect high-stakes decisions. Identify the areas of your life where processing speed matters most — finances, medical decisions, legal matters, driving — and build in extra safeguards. Get a second opinion before major financial moves. Bring a trusted person to important medical appointments. Be honest with yourself about your driving, especially at night, in new places, and in heavy traffic.

Stay socially engaged, but on your terms. Social isolation is a major risk factor for cognitive decline, but overwhelming social situations can drive withdrawal. Find social contexts that work for you — smaller groups, quieter settings, one-on-one conversations at your pace.

Keep learning, but differently. The ACTIVE trial suggests that the right kind of cognitive challenge can have lasting benefits. You don't have to "use it or lose it" in a generic sense — but targeted engagement with activities that challenge your processing speed (like the BrainHQ Double Decision exercises used in the ACTIVE trial) may offer genuine protection. This could be paired with physical exercise for a potentially synergistic effect.

The Science Is Catching Up

There's a hopeful thread running through all of this that's worth making explicit.

When Salthouse published his processing-speed theory in 1996, he gave us a powerful framework for understanding what was happening in the aging brain and why. But the tools available to act on that understanding were limited. Cognitive assessment was something that happened in a clinic, administered by a specialist, scored by hand, and typically deployed only after someone was already showing obvious problems. The idea of detecting subtle processing speed changes before symptoms appeared was science fiction.

When Germine launched TestMyBrain in 2008, the paradigm started to shift. For the first time, rigorous cognitive testing could happen anywhere, on any device, with anyone who had an internet connection. The data from millions of volunteers proved that digital assessment works. It showed that you didn't have to bring people into a laboratory to measure their brain function with scientific rigor.

What does this mean for you? The ability to detect subtle processing speed and cognitive changes during that 7-10 year window before a dementia diagnosis will become widely accessible, scientifically validated, and free. The tools that require a visit to a neuropsychologist's office could be available on your personal device.

This won't replace the need for expert guidance in navigating what comes next. A test that tells you your processing speed is declining doesn't tell you how to restructure your financial decision-making, or when to have the conversation about driving, or how to protect your autonomy while accepting appropriate support. But it could fundamentally change when those conversations begin — shifting them from reactive crisis management to proactive planning. And that shift, from late to early, from crisis to preparation, may be the most consequential change in how we approach cognitive aging in a generation.

The Bottom Line

Two things are happening at once. Your brain is gradually slowing down — a process as natural as your hair turning gray. And the world around you is speeding up, demanding faster responses to more information through more channels than at any point in human history. The collision of these two trends is the defining cognitive challenge of aging in the 21st century.

But the science is catching up. From Salthouse's discovery that processing speed is the central driver of cognitive aging, to Germine's revelation that different cognitive abilities peak on their own timelines, to building the tools to detect the earliest changes before symptoms appear. We are closer than we have ever been to understanding what's happening in the aging brain and intervening at the right time.

The evidence-based steps you can take today are clear: speed-of-processing training with booster sessions, regular aerobic exercise, cardiovascular risk management, and adequate sleep. And equally important, you can adapt your life to work with your changing brain — by giving yourself more time, curating your information environment, protecting your attention, reducing the need for simultaneous processing, safeguarding high-stakes decisions, and building the external structures that let your preserved reasoning and accumulated wisdom do their best work.

The world will keep speeding up. Your brain will keep its own pace. But with the right understanding and the right adaptations, you can continue to move through it with competence, dignity, and confidence. The music hasn't stopped. The tempo has changed. And you get to choose how you play it.

References

Coe, N. B., et al. (2026). Impact of cognitive training on claims-based diagnosed dementia over 20 years: Evidence from the ACTIVE study. Alzheimer's & Dementia: Translational Research and Clinical Interventions, 12(1). DOI: 10.1002/trc2.70197

Hartshorne, J. K. & Germine, L. T. (2015). When does cognitive functioning peak? The asynchronous rise and fall of different cognitive abilities across the lifespan. Psychological Science, 26(4), 433-443.

Salthouse, T. A. (1996). The processing-speed theory of adult age differences in cognition. Psychological Review, 103(3), 403-428.

Williamson, J. D., et al. (2019). Effect of intensive vs standard blood pressure control on probable dementia: A randomized clinical trial (SPRINT-MIND). JAMA, 321(6), 553-561.

The Science of Seeing Sooner: How Cutting-Edge Research Is Changing What's Possible for Families

Earlier this week, Georgetown University's Center for Security and Emerging Technology published an analysis of how prize competitions can accelerate AI-driven scientific discovery. They were examining which competitions best exemplify how we can use innovation challenges to advance science — and they chose the PREPARE Challenge as their lead example.

PREPARE — Pioneering Research for Early Prediction of Alzheimer's and Related Dementias — was a competition to improve detection of cognitive decline before a clinical diagnosis, by bringing together data scientists, clinicians, and AI researchers to build better prediction tools.

I led that challenge. It was one of the most rewarding experiences of my career — seeing a concept move from whiteboard to execution to a launchpad for translation into clinical practice. It came in on the tailwinds of a revolution that is shaking up how we treat diseases like Alzheimer’s disease.

A Revolution in Early Detection

For decades, the tools available for detecting Alzheimer's disease and related dementias were blunt instruments. By the time a diagnosis arrived, years of gradual change had already passed — years when families might have planned differently, acted sooner, or simply understood what they were seeing.

That reality is changing fast, across multiple scientific fronts at once.

The blood is talking. A new generation of blood tests can now detect the biological signatures of Alzheimer's disease — the protein buildups in the brain that were previously visible only through expensive brain scans or spinal taps. One of these tests received FDA approval in 2025. A simple blood draw can now provide information that once required a $5,000 imaging procedure. These tests aren't perfect screening tools yet, but they're transforming how clinicians evaluate cognitive concerns, especially when combined with other information.

Digital tools are catching what traditional tests miss. Researchers have developed computerized cognitive assessments that measure not just whether you got the answer right, but how you got there — the hesitations, the timing, the subtle shifts in processing speed that a paper-and-pencil test can't capture. Some of these tools can identify risk years before traditional screening methods raise a flag.

Voice and language patterns carry hidden signals. One of the most striking findings from recent research — including work that emerged through PREPARE — is that changes in speech and language can contain early markers of cognitive change. The way someone organizes a sentence, pauses between thoughts, or retrieves words can shift in detectable ways well before anyone in the room notices.

AI is connecting the dots. Machine learning algorithms can now integrate information across these different streams — blood markers, cognitive performance, speech patterns, medical history, even social and environmental factors — to build prediction models that outperform any single measure alone. PREPARE was designed to accelerate exactly this kind of work, and the results confirmed that combining diverse data sources yields meaningfully better early detection.

What the Science Can Do vs. What Families Actually Receive

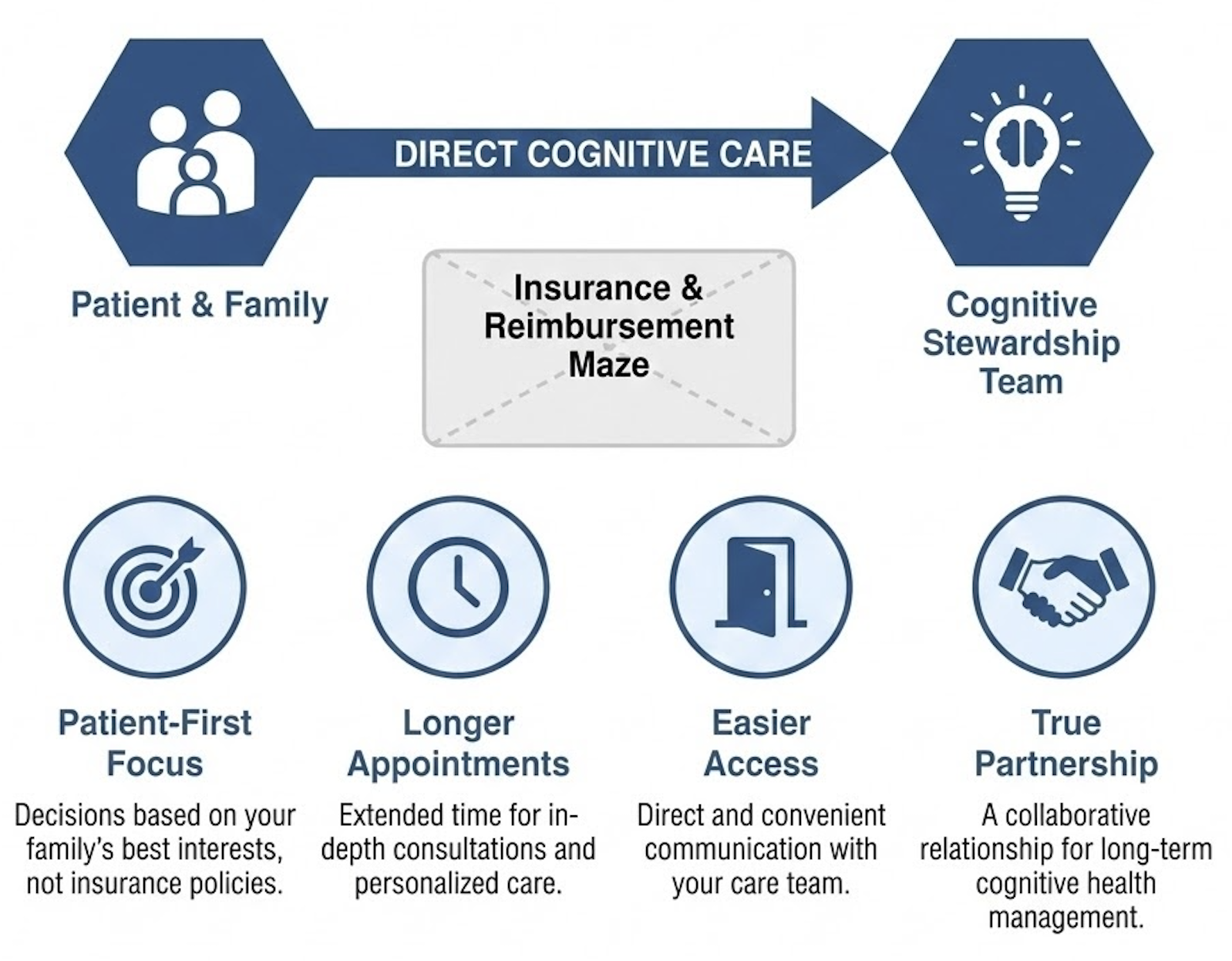

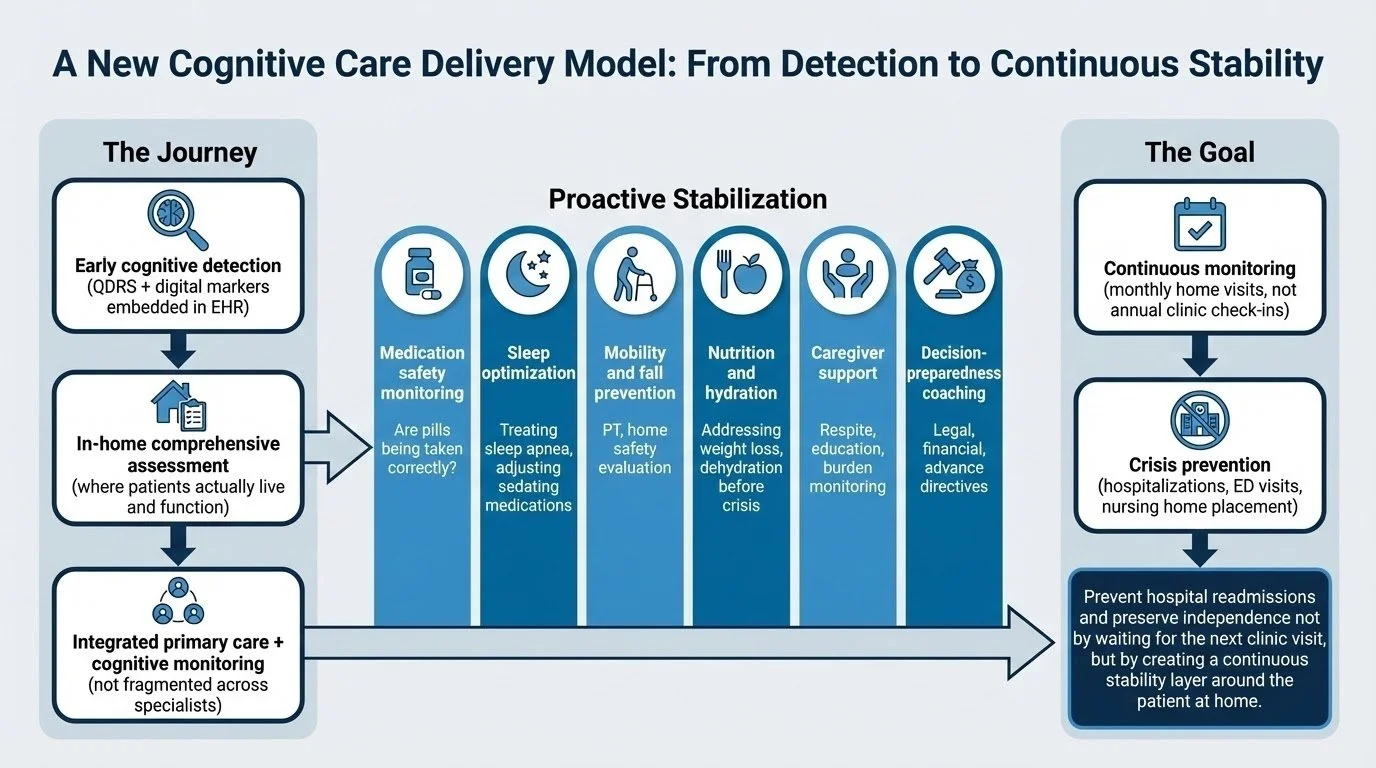

Here's the gap that motivated to start Treasure Coast Cognition.

This revolution in early detection is real. The science works. But almost none of it reaches families during the window when it matters most.

During this window, if you bring cognitive concerns to your doctor, you'll likely hear some version of: "It's probably normal aging. Let's keep an eye on it." That's not negligence — it's a system that isn't designed to act on early, ambiguous signals.

Meanwhile, the science now exists to characterize those early changes with far greater precision. Blood biomarkers can clarify biological risk. Sensitive cognitive assessments can establish baselines and track trajectories over time. Integrative analysis can distinguish between normal age-related variation and something that warrants closer attention and proactive planning.

The problem isn't the science. The problem is that no one is translating it for families in a way that leads to action.

Why I Built Treasure Coast Cognition

The neuroscience of cognitive aging, the early behavioral and biological markers of decline, the gap between research capability and clinical reality is the reason for Treasure Coast Cognition.

The clearest thing I learned was this: the families who navigate cognitive change best are the ones who start paying attention early — not after a crisis, not after a diagnosis, but during the window when understanding and planning are still fully available.

That's what Cognitive Stewardship is. It's the practice of proactively monitoring cognitive health, interpreting the signals that matter, and building a plan that protects independence, finances, and family relationships — grounded in the best available science.

Treasure Coast Cognition exists to be the bridge between what cutting-edge research can now detect and what your family actually needs to know and do. We take the same science that Georgetown just highlighted as a model for innovation, and we make it personal, ongoing, and actionable.

What This Means for You

If you're watching a parent, spouse, or loved one and wondering whether what you're seeing is "just aging" or something more — that uncertainty itself is a signal worth taking seriously.

Not because it necessarily means something is wrong. But because the science now exists to give you a clearer answer than "wait and see." And because the decisions that matter most — about legal authority, financial oversight, care preferences, living arrangements — are far better made with time and clarity than under pressure.

The revolution in early detection isn't coming. It's here. The question is whether your family has access to someone who can translate it into guidance that actually matters for your life.

That's the work we do.

"The Hidden Window" at the Harvard Club of Vero Beach

I'm honored to present "The Hidden Window" at the Harvard Club of Vero Beach next month. This talk explores one of the most important—and most overlooked—opportunities families face when a loved one's cognition begins to change.

Why This Matters

Most families wait for a dementia diagnosis before taking action. But by then, the window for proactive planning has largely closed.

Research consistently shows that cognitive and financial decision-making changes begin 7-10 years before a formal diagnosis. This is precisely when families can shape outcomes best—yet most don't realize they're in this critical window.

What We'll Cover

The presentation addresses four key areas:

The Hidden Window — Understanding when cognitive decline actually begins versus when it gets diagnosed, and why this gap matters for families.

Advances in Detection — New biomarkers, blood-based testing, and digital tools that are transforming early identification.

Proactive Stewardship — What it looks like to navigate cognitive change with a strategic plan rather than crisis management.

Practical First Steps — Concrete guidance for families who are noticing changes and wondering what to do next.

The Core Message

If you're noticing changes in a parent, spouse, or loved one—or if you're a professional advisor whose clients are asking difficult questions about cognitive capacity—the window for meaningful action is open now. Waiting has real costs: lost planning opportunities, financial vulnerability, family conflict, and missed treatment windows.

The good news? Proactive planning during this hidden window can prevent most of these outcomes while preserving autonomy and family harmony.

Join Us

This presentation is open to Harvard Club members and guests. If you're interested in attending, register through the Harvard Club of Vero Beach website. If you are not a Harvard affiliate, you are my guest!

Is Cognitive Stewardship Even About Cognition?

I'm a neuropsychologist. I spent twenty years studying how brains change over time. My practice is called Treasure Coast Cognition. The framework I've built is called Cognitive Stewardship.

So it's a fair question when I say: this work isn't really about cognition.

Or more precisely—cognition isn't the point. It's the entryway.

What People Think

People hear "cognitive" and make assumptions. They picture memory tests. Brain scans. A clinical report that says whether something is wrong.

Yes, comprehensive neuropsychological assessment is part of the product. It matters.

But families don't want video game scores. They come because they're watching someone they love change—and they don't know what to do about it.

The question that keeps us up at night is less "what's the diagnosis?" and more "what happens now?"

The Window

Here's what I've learned:

There's a window. It opens when someone first notices that something is different—in themselves or in someone they love. A moment of confusion that lingers. A decision that doesn't quite make sense. A capability that was there last year and isn't there now.

The window closes when clarity is gone—when the person at the center can no longer participate meaningfully in decisions about their own life.

Between those two points, everything important happens. Or it doesn't.

Families update legal documents or they don't. They have hard conversations about money, safety, and care—or they avoid them. They make proactive choices together, or they wait until crisis forces reactive ones.

The window is where agency lives.

Where Does Cognition Fit?

Cognition helps us predict when the window opens and when it closes.

Subtle cognitive changes are often the first signal that the window has opened—before a diagnosis, before a crisis, before anyone uses words like "dementia" or "decline." The changes might be barely noticeable to anyone outside the family. But they're there. And they mean something.

Cognitive assessment can tell you where someone is in that window. Not just "impaired or not impaired," but a much richer picture: Which capacities are preserved? Which are vulnerable? How much runway remains for complex decision-making? What's likely to change next, and when?

That information matters—not because a score is valuable in itself, but because it tells you how much time you have to do the work that actually matters.

The Work That Actually Matters

The work isn't cognition. The work is what you do with the window while it's open. It’s the lantern we take down the path as we navigate the decisions that matter most.

Structuring decisions that need to be made. Making decisions differently as things change over time. Creating permission for conversations that feel impossible. Helping families align when they see things differently. Building a plan that accounts for what's coming—not just what's here.

The questions at the center of this work aren't clinical. They're human:

Where does this end up?

Who decides when I can't?

How do I maintain dignity when things I could do become things I can't?

What can I settle now, while I still have clarity?

These questions belong to anyone watching their own capacity change—for any reason, at any pace. Cognition is one path into that territory. It's not the only one.

What Cognitive Stewardship Actually Provides

Structured partnership sounds abstract until you see what it replaces: fragmented information, undetected cognitive change disconnecting decision-making from behavior, behavior disconnected from what’s happening in the brain, and decisions made in a confused state, in a strange land, under pressure without a clear picture.

Here's what families get:

Clarity about where you stand. Not a screening test or a quick office visit—a comprehensive evaluation that maps cognitive strengths and vulnerabilities in detail. You stop guessing and start knowing.

A realistic timeline. Assessment tells you how much runway you have for complex decisions. That changes everything about what you prioritize and when.

Permission to have the hard conversations. An expert third party creates space for families to discuss what feels undiscussable. When I facilitate, concerns can surface without damaging relationships.

Decision guidance when stakes are high. Should we sell the house? Is it time to transfer financial management? Can Dad still drive safely? These aren't medical questions—but they have cognitive dimensions. You get expert perspective at the moments that matter.

A partner who tracks change over time. One evaluation is a snapshot. Longitudinal monitoring shows trajectory—so you're never surprised by what comes next. We align decisions and what matters most to where you are and where you will go.

Coordination with your existing team. Your estate attorney, financial advisor, and physicians need cognitive perspective to do their jobs well. We provide that.

What Changes

Families who engage in Cognitive Stewardship move from watching and worrying to acting with clarity. They stop waiting for crisis to force decisions. They use the window while it's open.

That's what you're purchasing: not a test, but a partnership through the years that matter most.

How Do I Know You Can Deliver This?

Fair question. Anyone can describe a philosophy. Execution is different.

This is the applied version of everything I've done. You'll tell me how it's working, and we'll deliver better results together.

A Letter To My Founding Families One Year Later

Dear Founding Families,

A year ago, I sent you a letter. I told you that you were taking a chance on something that was new, something we would build together. I told you I didn't take that lightly.

I want to tell you what happened.

What I Thought Would Happen

I had a plan. I had assessments and protocols and frameworks. I had ideas about how this would unfold—how the check-ins would work, what the family meetings would look like, when decisions would need to be made.

Some of that was useful. A lot of it had to change.

You taught me it was about us and the real work doesn't fit neatly into protocols. It happens in the phone calls that weren't scheduled, the questions that came up between meetings, the moments when something shifted and we needed to talk. It happens when a daughter calls because she noticed something new and isn't sure if it matters. It happens when a spouse says, for the first time, "I'm scared."

The frameworks helped. But the relationship is what made it work.

What Actually Happened

What would have happened without this year together? That's the hard thing about prevention—we can't prove what didn’t happen. We can't point to the crisis that didn't happen and say, "See? We stopped that."

But this was the journey we both observed.

There were family conversations that had been avoided because we named a framework for understanding what was happening. We watched adult children move from fear and frustration to something closer to clarity. We watched spouses stop carrying the weight alone.

We watched decisions get made at the right time. Not too early, when they would have felt like an overreaction. Not too late, when the options had narrowed. But in that window when there was still room to choose.

Some of our families are in a different place than they were a year ago. The changes are real, and they're hard. But we're moving through them together, with a plan, instead of scrambling to react.

That's not nothing. That's the whole point.

What I Got Wrong

I want to be honest with you about what didn't work the way I expected.

I underestimated how much time the in-between moments would take—and how important they would be. The scheduled check-ins were valuable, but the unscheduled ones often mattered more. I had to adjust how I structure my time to make room for that.

I overestimated how much families would use the documentation tools I created. Turns out, most of you preferred a phone call to a form. So we talked more and documented less formally. The information still got captured—just differently than I'd planned.

You helped me see what actually matters. The model is better now because of what you taught me.

What You Gave Me

You gave me proof that this works. Proof that we can see, feel, know, and take action around. The kind that comes from watching something unfold over time, seeing it works, and learning that it matters.

You gave me stories I'll carry with me. The hard conversations you had. The decisions you made. The grace you showed each other when things got difficult. I've learned more about how families navigate this passage from walking alongside you than from twenty years of academic research.

You gave me the chance to build something with you in my hometown. That's not a small thing. Family is everything. Family is here. You made it real.

And you gave me your trust—before there was any reason to trust, before there was evidence that this would work. That's a gift I won't forget.

What Comes Next

For most of you, the journey isn't over. There are still decisions ahead, still transitions to navigate, still hard conversations to have. I'll be here for those.

For the practice, there are more families now. They found me because you told them about what we built together. Some of them are at the beginning of the path you've been walking. I'm better able to help them because of what I learned from you.

I don't know exactly what the next year holds. But I know what we did together, and I know it's working. You showed me that. Because you did, other families won't have to.

Thank you for trusting me with your family's story. Thank you for teaching me what this work actually looks like. Thank you for being patient while we figured it out.

I'm grateful. More than I can easily say.

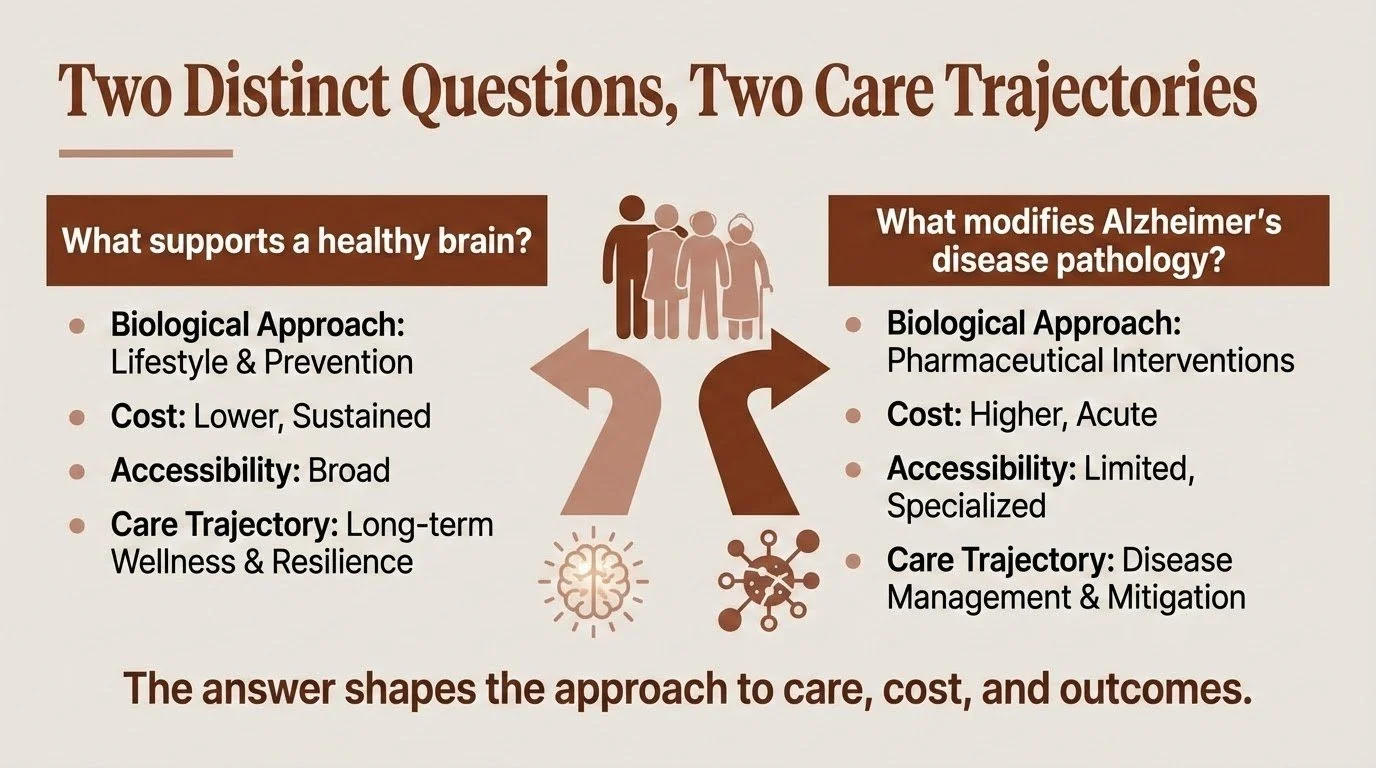

What Changes Brain Health vs. What Changes Alzheimer’s

If you've read about Alzheimer's disease, you've probably encountered two contradictory messages.

The first: Do these ten things and you can prevent Alzheimer's.

The second: There's nothing you can do — and the drugs don't really work anyway.

As with most false dichotomies, both are wrong. And the confusion between them causes real harm — leading families toward either false hope or premature resignation, neither of which serves them.

The problem is that most conversations about brain health blur together two fundamentally different questions:

What supports a healthy brain?

and

What modifies Alzheimer's disease pathology?

These aren't the same question. They differ not only in biological approach but also in cost, accessibility, and what they can realistically deliver. Understanding why — and what that means for you and your family — is one of the most important things I can help clarify.

Brain Health: Building Resilience

When researchers talk about lifestyle factors and brain health, they're describing something real and evidence-based. Regular physical exercise, quality sleep, cognitive engagement, social connection, managing vascular risk factors — these work.

At a 2019 National Academies workshop on brain health, I proposed a working definition of resilience that captures what we're actually building: A resilient person has a variety of neurocognitive tools and networks that can be activated in response to challenges, and can adaptively deploy these tools to optimize function when facing environmental and psychological demands. The Collaboratory on Research Definitions for Reserve and Resilience in Cognitive Aging and Dementia has developed consensus definitions distinguishing cognitive reserve, brain maintenance, and brain reserve — with resilience as an overarching framework. Resilience isn't about preventing damage — it's about having options when damage occurs.

The evidence for building resilience is solid. Large trials like FINGER and POINTER have demonstrated improvements in cognitive performance and risk profiles through structured lifestyle interventions. We continue to learn how, including how cognitive reserve builds a more adaptable brain that can compensate longer when damage occurs; vascular health that ensures adequate blood flow; and reduced systemic and neuroinflammatory burden associated with slower decline.

But here's the crucial distinction: these interventions build resilience. They may delay the expression of symptoms. They reduce risk. What they don't do — at least not directly — is stop the molecular machinery of Alzheimer's disease itself.

Importantly, no one "fails" their way into Alzheimer's disease. Genetics and biology matter enormously, even when people do everything right. The lifestyle work is worth doing — but it's not a guarantee, and families shouldn't carry guilt when decline happens despite their best efforts.

And critically, these interventions are accessible. They don't require specialized facilities, insurance approval, or infusion centers. The cost is measured in effort and consistency, not dollars.

Disease Modification: Targeting the Pathology

Alzheimer's disease involves a specific pathological process — the accumulation of amyloid plaques and tau tangles that progressively damage brain tissue. For decades, researchers have worked to develop treatments that target this cascade directly.

The timeline of progress here is worth understanding, because much of what we can now measure and treat has emerged remarkably recently.

The biomarker revolution: Until the past few years, confirming Alzheimer's pathology required either invasive lumbar punctures for cerebrospinal fluid analysis or expensive PET imaging costing thousands of dollars with limited availability. That's changing rapidly. Blood-based biomarkers — particularly phosphorylated tau at position 217 (p-tau217) — can now detect Alzheimer's pathology with accuracy often approaching PET imaging in research cohorts. Studies show p-tau217 levels begin rising more than 20 years before symptom onset, providing an unprecedented window into what's happening biologically. These tests are becoming available commercially for around $200, though clinical standards for interpretation and follow-up are still evolving.

Detection enables better decisions — even when treatment options are limited. Knowing what you're facing allows for realistic planning, targeted monitoring, and informed choices about emerging therapies.

Disease-modifying therapies: Anti-amyloid antibodies like lecanemab (Leqembi) and donanemab (Kisunla) represent genuine scientific progress. They can reduce amyloid burden in the brain. Clinical trials have shown modest slowing of decline in people with early-stage disease — approximately 25-35% slowing of progression over 18 months.

But "modest" is the operative word. These are not cures. They don't reverse damage already done. Their effects, while statistically meaningful, translate to relatively small differences in day-to-day function over the study periods. Some individuals and families experience noticeable benefit; others experience none. And the treatments come with real risks — brain swelling (ARIA-E) and microbleeds (ARIA-H) requiring careful monitoring with regular MRIs.

A recent episode of the Penn Memory Center's Age of Aging podcast reviewed where things stand after the 2025 Clinical Trials on Alzheimer's Disease (CTAD) conference. The picture is nuanced: anti-amyloid therapies show consistent but modest effects, while hoped-for breakthroughs in other approaches — like GLP-1 medications — have so far disappointed.

Cost and accessibility: This is where disease modification diverges sharply from brain health approaches. Lecanemab costs approximately $26,500 per year; donanemab runs about $32,000. Medicare covers these drugs, but patients face significant out-of-pocket costs — roughly $5,000-6,600 annually after deductibles, plus costs for required monitoring MRIs and infusion visits. The treatments require biweekly (lecanemab) or monthly (donanemab) infusions at specialized centers, genetic testing for APOE status, and ongoing safety monitoring.

One recent improvement: the FDA approved a subcutaneous autoinjector formulation of lecanemab (Leqembi Iqlik) in late 2025 for maintenance dosing. After completing 18 months of IV infusions, patients can now switch to weekly at-home injections — a 15-second self-administered dose that eliminates ongoing infusion center visits. And a supplemental application for subcutaneous initiation treatment — which would allow patients to bypass the IV infusion phase entirely and start treatment at home — was completed in November 2025 and is currently under FDA review.

If approved, this would represent a meaningful shift in accessibility. But for now, many families — particularly those in rural areas or without supplemental insurance — still face significant barriers to starting treatment, regardless of clinical appropriateness.

What may be coming: The next generation of therapies aims to address current limitations. "Brain shuttle" technologies — bispecific antibodies engineered to cross the blood-brain barrier via transferrin receptor binding — show early promise for improving drug delivery while potentially reducing side effects. Roche's trontinemab, which uses this approach, has shown rapid amyloid clearance at lower doses with encouraging early safety data, including very low rates of ARIA-E. In early trials, 91% of participants on the higher dose became amyloid-negative within six months.

These results are early and focused on biomarker outcomes; whether this translates into meaningful clinical benefit remains to be seen. But the direction is promising — better delivery, broader brain distribution, and potentially improved safety profiles.

Why Both Matter — And Why the Distinction Matters More

Here's what I want families to hold:

Do the lifestyle work. It's not nothing. Building cognitive reserve, protecting vascular health, staying engaged — these create real protection. They may give you more good years, more functional capacity, more time. They're accessible to nearly everyone, regardless of insurance status or geography.

And understand that lifestyle isn't a cure. It doesn’t look like exercise or crossword puzzles alone will stop tau from spreading. These are different biological problems requiring different solutions.

Take disease-modifying options seriously — but realistically. For appropriate candidates, anti-amyloid therapies represent a genuine, if modest, advance. But they're expensive, require significant infrastructure, carry real risks, and deliver incremental rather than transformative benefit. They're one tool, not a solution.

The danger comes from conflating these approaches. Families who believe lifestyle alone prevents Alzheimer's may delay necessary planning or feel blindsided when decline happens despite doing "everything right." Families who pin all hope on medications may be devastated by modest results — or may dismiss the meaningful protection that lifestyle factors actually provide.

Neither position serves you.

What This Means for Your Family

People living with Alzheimer's consistently tell us two things matter most: being treated as whole people — not diagnoses — and having time to make decisions while their voice still counts. Biomarkers and treatments matter only insofar as they support those goals.

Navigating this territory requires holding complexity — understanding what's within your control, what isn't, and how to plan wisely for both. It means neither over-relying on prevention promises nor surrendering to fatalism. It means understanding that the science is advancing rapidly, that what we can measure and treat today was impossible five years ago, and that thoughtful engagement beats both wishful thinking and despair.

This is part of what I help families do: make sense of the science as it actually stands, understand what it means for their specific situation, and build a path forward that accounts for both what we know and what remains uncertain.

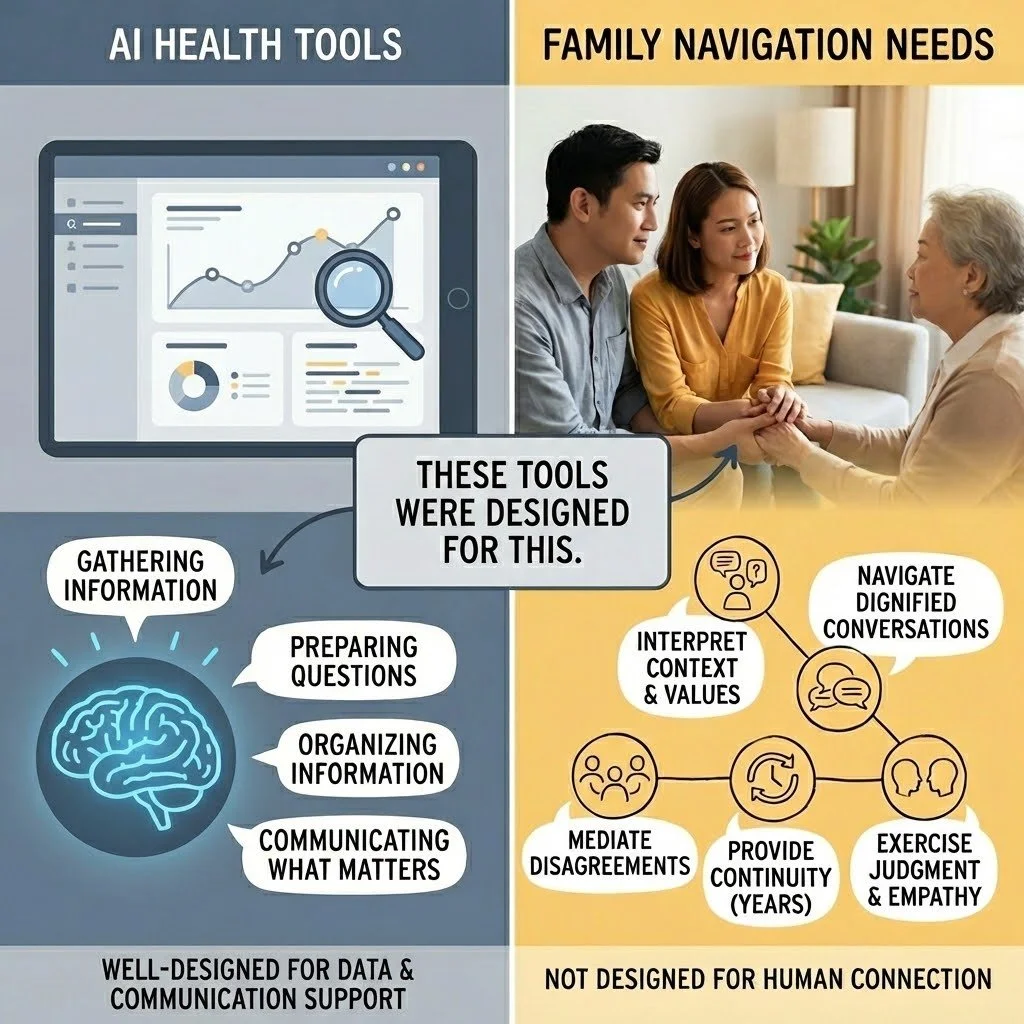

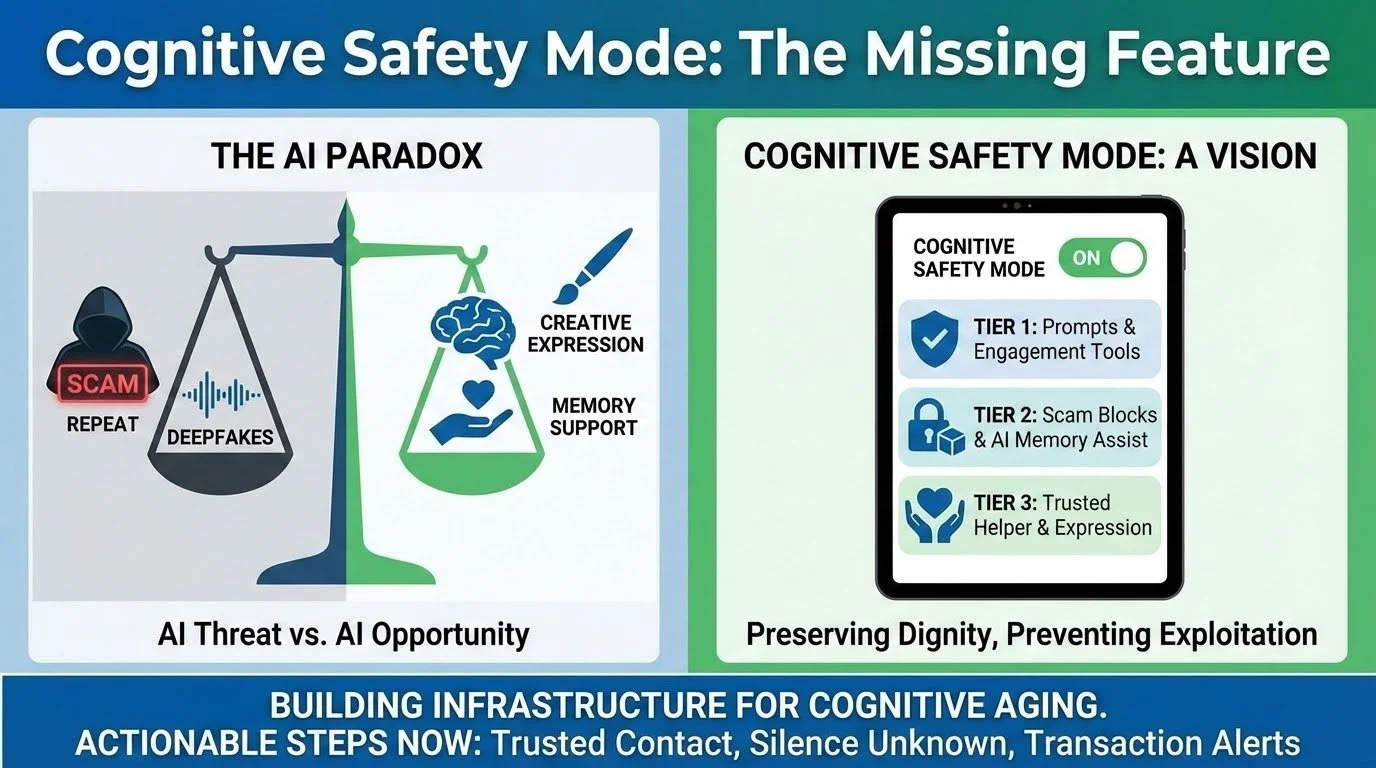

AI Can Help Interpret Your Health Data. That Is Not The Problem That Matters Most.

The new health tools from OpenAI and Anthropic are impressive. They also may not address what matters most for families navigating cognitive change.

OpenAI and Anthropic—two of the biggest names in AI—have launched health products within days of each other. Both let you connect your medical records and get personalized health insights. The various AI chatbots and tools available are impressive, they feel different, they have helped me do and understand things quickly and in new ways, but they have often convinced me of things that were not true, too.

This may remind some of us of the early WebMD and IBM Watson days. WebMD made health information accessible but didn't solve complex health decisions. IBM Watson promised AI-powered clinical intelligence but did not and was never accessible to regular people anyway. Now OpenAI and Anthropic have essentially combined both—AI-powered analysis that anyone can access.

Twenty years ago, WebMD was supposed to transform how we understood our health. And in many ways, it did—millions of people gained access to medical information that was previously locked away in textbooks and doctor's offices. It was a real improvement. It also didn't replace the need for doctors, didn't solve the problem of navigating complex health decisions, and didn't help families figure out what to actually do when facing something serious.

These new AI tools are more sophisticated than WebMD. They can synthesize your personal health data, translate medical jargon, and provide tailored responses. For many health questions, they'll be genuinely useful.

But if you're an adult child watching your parent struggle—wondering whether it's time to have the conversation about driving or finances, trying to coordinate care from a distance while family members disagree about what to do—you may find that these tools, like WebMD before them, don't quite address the problem you're actually facing.

What These Tools Were Designed For

Let's start with what these tools do well, because they do some things very well.

They were designed to help individuals understand their own health data. They pull together lab results from multiple providers. They translate medical terminology into plain language. They can identify patterns across health metrics, test results, and clinical notes. They're available at 2am when you're worried about a test result.

OpenAI reports that 230 million people ask ChatGPT health questions every week. Anthropic's head of life sciences captured the appeal: "When navigating through health systems and health situations, you often have this feeling that you're sort of alone and that you're tying together all this data from all these sources."

That's a real problem, and for many people—particularly those managing their own health with full cognitive capacity—these tools offer a real solution. They were well-designed for that purpose.

The question is whether that purpose matches what families navigating cognitive change actually need.

What These Tools Weren't Designed For

These tools were built on certain assumptions. The user is managing their own health. The user can evaluate whether the information seems accurate. The user can take action on what they learn. The user has access to the relevant health data.

For families navigating cognitive change, those assumptions often don't hold.

The person who needs help may not recognize they need it. Cognitive decline often impairs insight—a phenomenon clinicians call anosognosia. Your father may not notice the changes you're seeing, or he may be frightened and expressing that fear as anger when you raise concerns. AI can synthesize his medical records. It wasn't designed to help you navigate a conversation with someone who doesn't believe anything is wrong. The models weren’t trained on anosognosia data and I have not seen research that shows the models perform well in clinical cases involving social interaction when one partner has limited insight.

You may not have access to the data. These tools assume you're connecting your Apple Health, your patient portal, your lab results. But you're trying to help someone else—someone who hasn't given you access (or not full access), who may not remember their passwords, whose medical information you might legally be unable to see. Medical records often don’t even include the data that matters most for managing care decisions. Can you get an answer? Yes. Is that answer accurate? Unclear. Is that answer helpful? Unclear. Is that answer harmful? Unclear.

Family decisions aren't individual decisions. Your brother thinks you're overreacting. Your sister thinks Mom should be in a facility. You're trying to coordinate care while managing everyone's emotions, your own guilt, and a lifetime of family dynamics. These tools were designed for one person asking about their own health, not for the complexity of family decision-making.

Information wasn't the bottleneck. You've probably already Googled more than you wanted to know about cognitive decline. You've read the Alzheimer's Association materials. You may have a folder of articles about power of attorney and warning signs. The information exists. What you need is help figuring out what it means for your family and what to actually do about it.

What the Data Can't Tell You

AI health tools are only as good as the data they're trained on and the data they can access. Both have significant limitations for families navigating cognitive change.

Training data reflects healthcare's existing patterns. These models learned from existing medical records, research studies, and health information. If the healthcare system has historically under-diagnosed cognitive decline in certain populations, dismissed family concerns, or failed to document early warning signs, AI trained on that data will inherit those blind spots. The models are excellent at pattern recognition—but they can only recognize patterns that exist in their training data.

Medical records capture what gets documented, not what's happening. Your mother's medical record shows her last visit was "unremarkable." It doesn't capture that she's been hiding unpaid bills for six months, that she gave $5,000 to a phone scammer last week, or that she no longer recognizes her grandchildren's names. AI can only access the slice of reality shared with it.

Some populations are systematically underrepresented. A widely-cited study found that a common healthcare algorithm underestimated the health needs of Black patients by using prior healthcare spending as a proxy—encoding historical inequities into automated recommendations. When certain communities are underrepresented in training data, AI tools may work less well for exactly the populations that already face barriers to care.

Rural, older, and less digitally-connected populations may be excluded entirely. Nearly 30% of rural adults lack access to AI-enhanced healthcare tools. Adults over 75 are most likely to struggle with digital interfaces and most concerned about data privacy. The people most likely to be navigating cognitive changes are often least able to benefit from these technologies.

What Families Actually Face

Here's what I've learned about what families are actually navigating:

The conversations are harder than the information. Knowing your father's executive function has declined is one thing. Telling him he shouldn't manage the family finances anymore—without destroying your relationship—is something else entirely. These conversations require timing, judgment, and deep knowledge of family dynamics that no tool can provide.

The medical system often doesn't help until there's a crisis. You've mentioned your concerns to doctors. They did a brief cognitive screen, said "normal for age," and moved on. Meanwhile, you're watching someone make increasingly risky decisions and no one seems to take it seriously. AI tools that connect to medical records from those same dismissive appointments don't change this dynamic. AI tools that don’t have the information that matters most cannot integrate that information into guidance and care.

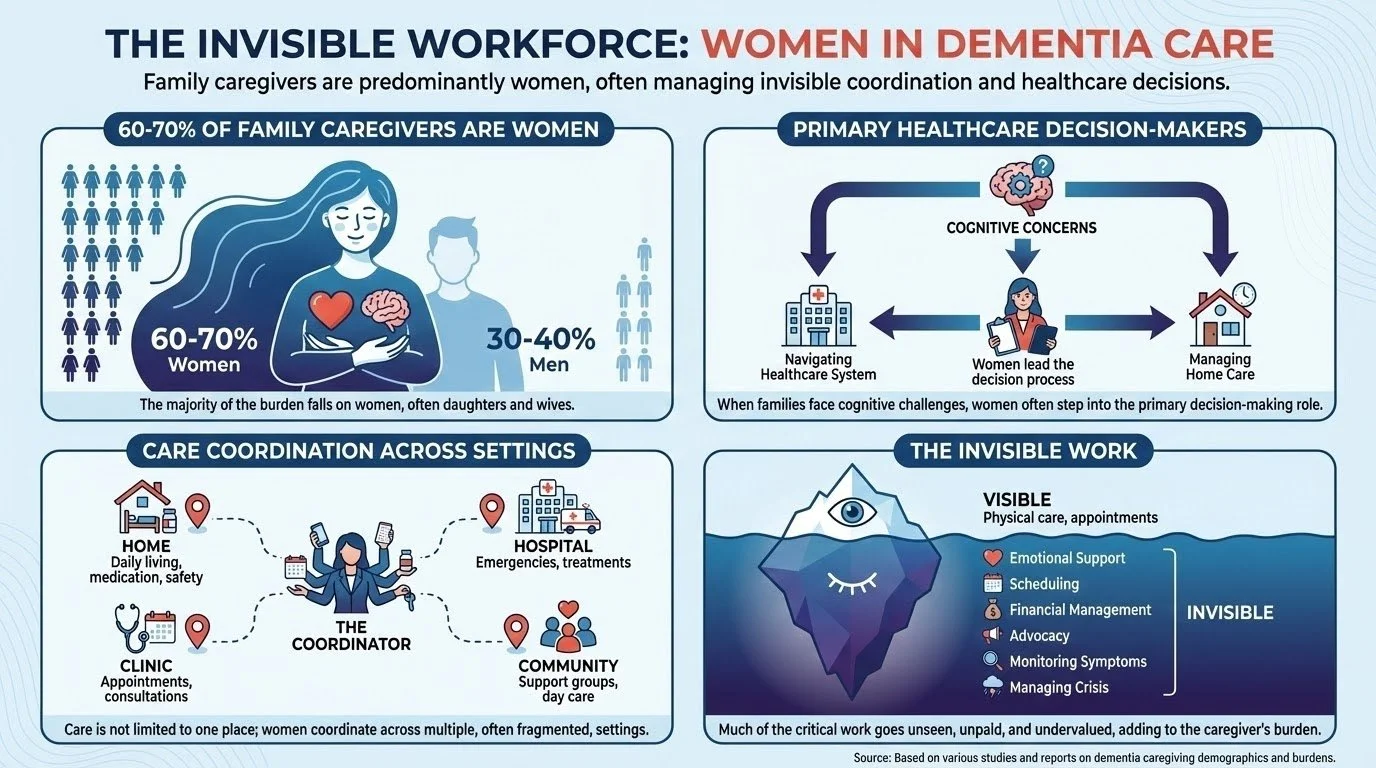

Caregiving is relentless and invisible. Caregiving is hard. The role demands constant vigilance, difficult decisions, and managing someone who may resent your help. Caregivers describe becoming "like a manager"—deciding everything on behalf of another person while that person often fails to understand why their autonomy is being taken away. This isn't an information problem. It's a human problem.

What you need changes over time. The questions you face in year one are different from year three or year seven. Decisions about healthcare, living arrangements, and finances unfold through ongoing negotiation within families. If the AI tool cannot accurately track those changes over time or treats each question in isolation or without full context, you may not get the guidance and support you need.

Where AI Fits—And Where It Doesn't

AI tools have been incredibly useful in some aspects of my work. They're useful for organizing information, troubleshooting, idea generation and testing, drafting documents, and surfacing patterns across work tasks and items. They help me like a clinical or research assistant I can bother at 2am. I see AI health tools serving a useful purpose in the future if all the risks and concerns are adequately addressed and if people want to use these tools. They may help surface data earlier, prepare better questions for appointments, and reduce some information-gathering burden.

But I see major gaps for what families navigating cognitive change most need:

Interpret data in the context of a specific family's situation, values, and dynamics

Navigate the conversations that preserve dignity while acknowledging hard truths

Mediate disagreements between family members with different perspectives

Provide continuity over a journey that spans years, not queries

Exercise judgment about when to push, when to wait, and what this particular family can actually live with

This isn't a criticism of AI. These tools were well-designed for what they were designed for. They just weren't designed for this.

The Trust Question

Only 5% of Americans say they trust AI "a lot" for health decisions. Trust in AI health information is actually declining—30% now express distrust, up from 23% two years ago. Most people still view their doctor as the most trusted source. It is less clear how people will view their doctors when they partner with AI to provide care.

That skepticism may be healthy. These tools are new. They haven't yet demonstrated reliability in high-stakes, complex family situations. For families facing cognitive decline—where the stakes involve autonomy, dignity, safety, and relationships that span decades—caution seems appropriate.

The question isn't whether AI is good or bad. It's whether these particular tools, designed for these particular purposes, address what families actually need. That families and providers understand the risks and that families and providers know how to use the tools to deliver the most benefit for what matters most to families. This means adequately accounting for biases in the training data, models, and risks that come with turning over aspects of care to a new technology.

This isn't about AI competing with doctors or AI being forced on providers and families. It's about filling a gap that neither fills: helping families interpret what's happening in context, navigate the conversations that matter, and make decisions they can live with over the years this unfolds. The stakes are high to do this in the right way centering the families that are navigating these changes together.

I Want to Play More Golf with Men Who Provide Care

A man I spoke with recently is navigating his wife's early cognitive changes. He's done everything right by the planning playbook—the logistics are solid: finances, decisions, problem-solving. He’s got that. That's the role he knows.

During our conversation, he mentioned a friend who got a care companion so he could play more golf. I have a complicated history with golf, so it is not the place I go for therapy. However, we weren’t talking about golf, we were talking about care. The care for his wife he provides and the support he needs. What I heard underneath: I don't want to escape from this. I want to know how to be in it.

What if he could play more golf with men who provide care?

What the Research Actually Shows

More men are finding themselves in the caregiving role than in prior generations yet most of what we know about supporting caregivers comes from research on women.

When researchers look at male and female dementia caregivers, the findings are more nuanced than you might expect.

Quantitatively, the differences are modest. Across studies, the measurable differences between male and female caregivers are smaller than stereotypes suggest.

Qualitatively, something different emerges. When researchers interview male caregivers, they describe distinct approaches to help-seeking. Men tend to focus on functional tasks first. They're less likely to identify as "a caregiver." They often wait for a kind of permission—from the person with dementia, from a professional—before seeking services. They may not know what the right services look like or who provides what their partner needs. They're patterns shaped by life experience that have real implications for how we design support.

What Male Caregivers Actually Face

Loneliness and isolation. This may be driven by reluctance to leave their loved one alone, friends gradually dropping away, and limited social networks that shrink further during caregiving.

Priority on maintaining couplehood. Male caregivers appear more concerned than female caregivers about being separated from their spouse. They may be reluctant to plan for respite care. Preservation of the relationship itself may take priority.

An unfamiliar role. For men socialized in traditional gender roles, caregiving represents new territory. Men may not see themselves as caregivers, but more importantly, men may not have been socialized to provide care. They may not know how to flex their emotional intelligence in quite this capacity, direction, or in such a sustained manner.

What the Evidence Says Actually Helps

In 2020, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality published a comprehensive systematic review of 627 studies on dementia care interventions. In 2021, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine used this review to develop national recommendations.

The findings were sobering—and clarifying.

Only two types of interventions showed evidence of benefit strong enough to recommend for broad implementation:

Multicomponent caregiver interventions like REACH II (Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer's Caregiver Health), which combines education, skills training, problem-solving strategies, stress management, and support—delivered through a mix of in-home sessions, phone support, and group discussion. Low-strength evidence shows this approach reduces caregiver depression.

Collaborative care models that use multidisciplinary teams to integrate medical and psychosocial care. Low-strength evidence shows these improve quality of life for people living with dementia and reduce emergency room visits.

For all other interventions—including support groups as standalone approaches—the evidence was insufficient to draw conclusions. This doesn't mean they're ineffective. It means we can't yet determine from the research whether they work, for whom, or under what circumstances.

The National Academies report put it plainly: given the complexity of dementia care, mixed results across studies may reflect differences in populations, settings, or how interventions were implemented—not necessarily that the interventions don't work.

Translation: "Just talk about it" is rarely enough on its own. What the evidence supports is a playbook—education, skills, problem-solving, and support—customized to the situation you're actually in.

Bridging the Gap for Men

Here's what we don't yet have: rigorous research testing whether adapting interventions specifically for male caregivers improves outcomes. A 2023 systematic review explicitly noted that none of the digital education studies examined had reported outcomes separately by gender or adapted their approaches for male needs.

That's a significant gap. We're largely working from reasonable inferences rather than proven approaches.

That said, several principles emerge from what we do know:

Start with the practical. Men in caregiving situations often focus on functional issues first. Building rapport may work better when conversations begin with concrete challenges—managing medications, handling repeated questions, navigating the healthcare system—rather than asking about emotional impact directly.

Frame learning as skill development. The evidence shows psychoeducation works. For some men, framing this as building competence in a new domain may resonate better than framing it as processing emotions.

Create space for connection without forcing it. Qualitative research suggests some male caregivers value being around other men in similar situations. But the research does not conclusively show that men-only groups are necessary—only that some men find them valuable.

Address loneliness directly. Given how consistently loneliness appears in the research, any support for male caregivers should explicitly address social connection and isolation.

What This Man Might Actually Need

The man I spoke with doesn't need someone to tell him what to plan. He's done the planning. Based on what the evidence suggests, what might help him is:

Understanding what's changing—translating the science of cognitive change into something he can work with

Concrete strategies—what to say when she asks the same question, how to respond when she doesn't recognize familiar places, when to adjust expectations

A map of what's coming—the predictable decision points he'll face, and when the window to address them starts closing

Permission to struggle—hearing that this is hard, that finding it hard doesn't mean he's failing

Someone in his corner—not for one consultation, but for the journey

References

Butler M, Gaugler JE, Talley KMC, et al. Care Interventions for People Living With Dementia and Their Caregivers. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 231. AHRQ Publication No. 20-EHC023. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; August 2020.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Meeting the Challenge of Caring for Persons Living with Dementia and Their Care Partners and Caregivers: A Way Forward. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2021.

Pöysti MM, Laakkonen ML, Strandberg T, et al. Gender differences in dementia spousal caregiving. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;2012:162960.

Sjøvoll TH, et al. "Seeking a Bridge Over Troubled Waters": Older men's experiences as dementia caregivers—A meta-synthesis. BMC Geriatr. 2025.

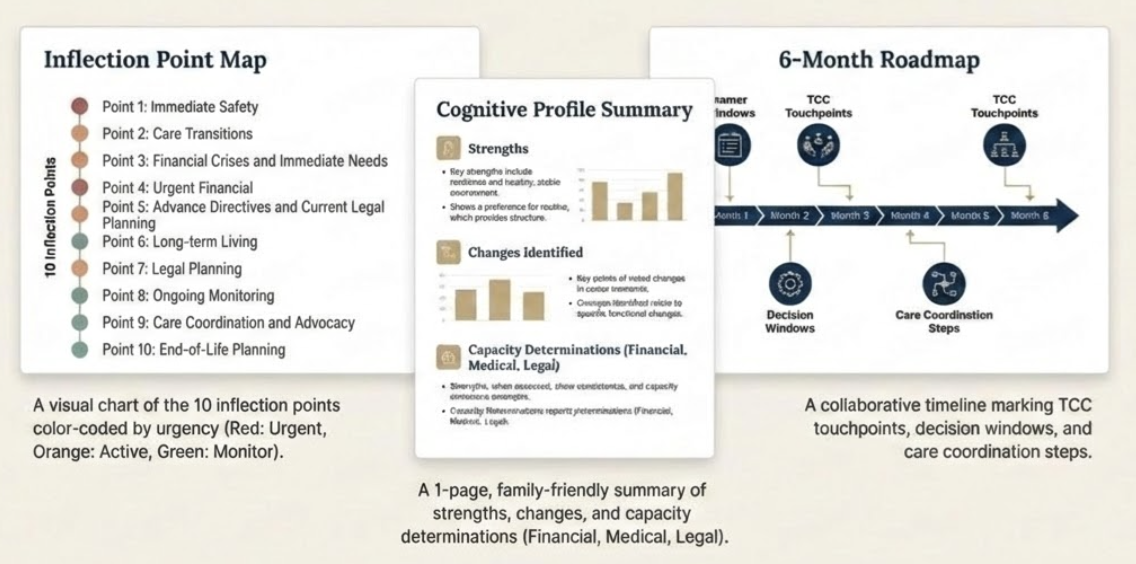

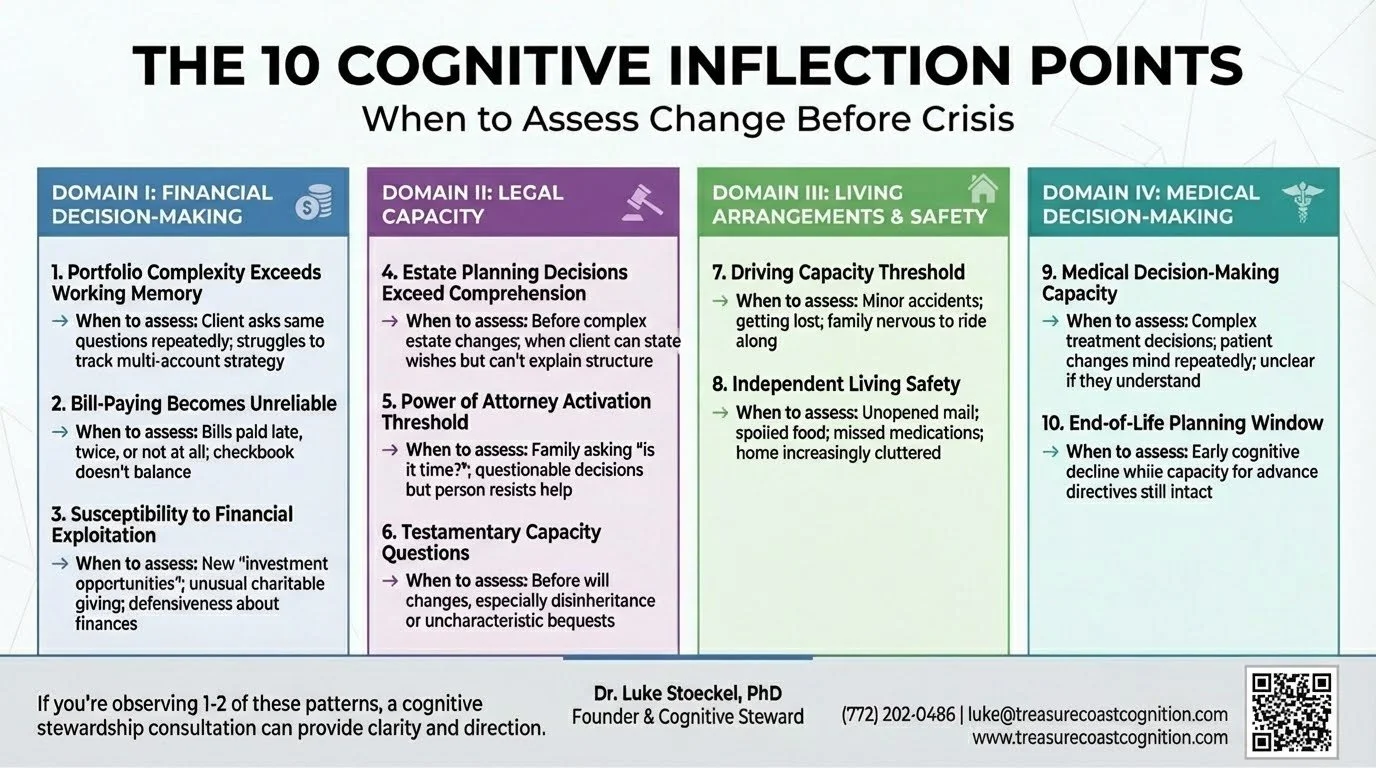

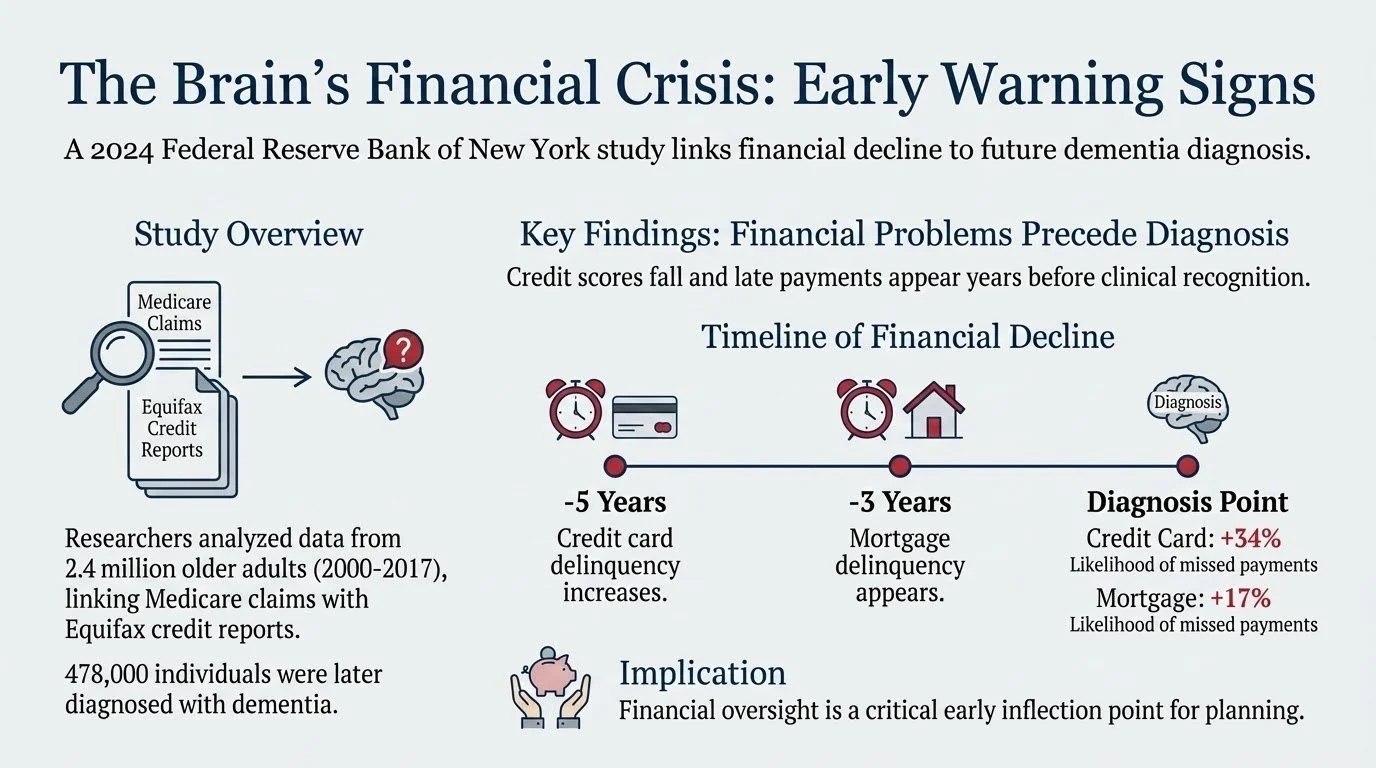

An inflection point is a moment when a relatively small cognitive change creates disproportionate risk for poor outcomes.

These aren't binary thresholds where capacity suddenly disappears. They're gradient transitions where specific cognitive functions decline in ways that impact specific real-world decisions.

The framework identifies 10 predictable decision points that most families encounter during cognitive transitions. If you recognize them early, proactive planning is still possible. If you miss the window, you're managing crisis.

Here's what to watch for:

DOMAIN I: Financial Decision-Making

1. Portfolio Complexity Exceeds Working Memory

What to watch for:

Difficulty tracking multiple accounts

Conversations with advisors require more repetition

Struggling to synthesize overall investment strategy

Increasing reliance on written summaries

The cognitive change: Working memory decline—difficulty holding and manipulating multiple pieces of information simultaneously

Why it matters: The person may still be able to discuss individual investments, but complex portfolio rebalancing, tax strategy, and multi-year planning may exceed current capacity. Without recognition of this change, they may agree to strategies they don't fully understand or resist necessary changes because they can't track the reasoning.

The decision point: Should we simplify the portfolio to match current capacity, or add oversight while maintaining complexity?

2. Bill-Paying Becomes Unreliable

What to watch for:

Bills paid late, twice, or not at all

Checkbook doesn't balance

Confusion about automatic payments

Insistence they paid something they didn't

The cognitive change: Executive function and prospective memory decline—difficulty remembering to perform future tasks and monitoring what's been completed

Why it matters: Bill-paying errors are often among the first visible signs that cognitive changes are affecting instrumental activities of daily living. Late payments can damage credit scores, duplicate payments drain accounts, and unpaid bills create legal consequences. More importantly, if bill-paying is compromised, more complex financial management is almost certainly at risk.

The decision point: Is this occasional forgetfulness that can be addressed with organizational systems, or is this evidence of declining capacity that requires direct oversight?

3. Susceptibility to Financial Exploitation

What to watch for:

Sudden interest in questionable "investment opportunities"

Difficulty ending sales calls

Charitable giving disproportionate to values or means

New "advisors" the family hasn't met

Defensiveness when questioned about financial decisions

The cognitive change: Decline in judgment, emotional regulation, and social cognition—particularly the ability to detect deception, assess risk, and resist persuasion

Why it matters: Elder financial exploitation is estimated to cost older adults billions of dollars annually, with individual losses often averaging $120,000. Once exploitation begins, it tends to escalate. Victims are often too embarrassed to report it, and by the time family members discover it, significant assets may be gone.

The decision point: Can they still manage financial relationships independently, or do they need protective oversight while preserving as much autonomy as possible?

DOMAIN II: Health & Medical Decision-Making

4. Medication Management Becomes Unreliable

What to watch for:

Medications taken at wrong times or in wrong doses

Pills remaining in organizers days after they should have been taken

Confusion about which medication treats which condition

Duplicate or missed doses

The cognitive change: Executive function and prospective memory decline affecting the ability to follow complex medication regimens

Why it matters: Medication non-adherence is associated with increased hospitalizations, disease progression, and preventable complications. For conditions like hypertension, diabetes, or heart disease, inconsistent medication use creates serious health risks. It's also an early indicator that other complex health management tasks may be compromised.

The decision point: Can medication management be maintained with organizational systems and reminders, or is direct oversight required?

5. Complex Medical Decisions Exceed Comprehension

What to watch for:

Struggling to weigh treatment trade-offs

Asking appropriate questions but difficulty retaining information

Changing mind repeatedly about treatment preferences

Physician uncertain whether they truly understand implications

The cognitive change: Decline in complex reasoning, future orientation, and ability to weigh probabilistic outcomes